This research piece was commissioned by, and conducted in conjunction with, the Wildland team and funded via a grant from Golem Foundation. It was written in Q2 2022. Please check that information is accurate or up-to-date at the time of reading.

This blog forms Part 1 of 2, on analyzing the concepts of “User-Defined Organization” and “Proof-of-Usage” as proposed by Wildland.

PART 1: Introducing Wildland, “User-Defined Organization”, and Limitations of Current Design Proposal

This piece summarizes a research sprint conducted by the governance research team at BlockScience on the project Wildland, “a personal docker container for your data”, whose founding team proposes a storage marketplace and user-controlled governance as part of the design of the Wildland ecosystem. We are very interested in the prospects of the Wildland protocol and have identified numerous possible areas for improvement of the UDO concept that accompanies the protocol itself in the following analysis. We highlight some of the reasons that governance is hard, and why innovating on governance and a product at the same time, when including a community, is harder still.

What is a UDO?

UDO stands for ‘User Defined Organization’. It is an institutional framework proposed by Wildland (a project by Golem Foundation) in the whitepaper, and later on, the blog, to try and improve on some of the shortcomings of the general idea of “Decentralized Autonomous Organizations”.

According to the Wildland whitepaper, the UDO is separate from the Wildland protocol, which aims to give users the authority to direct the spending of value generated from the Wildland marketplace, to improve the underlying protocol. In essence, UDOs are more a reaction to the gatekeeping and censorship of existing information platforms than the general concept of DAOs. Usage is measured in “Proof-of-Usage” (PoU) tokens earned through spending on storage in the Wildland marketplace, and equates to governance power in the UDO, to spend the treasury, determine the parameters of the marketplace payments systems, PoU token generation, and internal governance of the UDO itself. Some of the team points out that this could instead be termed a “User-Managed Organization”, and hopes that other protocols will utilize and build on the idea of UDOs to incorporate their own.

The rest of this analysis of the UDO concept explores some of the following questions:

- Who are the users?

- What is being organized?

- Is the organization an entity and/or an ongoing process (noun or a verb)?

- Does the act of “defining” organization change depending on the meaning of “organization”, and if so, in what ways?

Further context is required and an important assumption to question is: do users want the responsibility of self-organizing to allocate funding resources in the first place?

Beyond that, coordinated organization (as a verb) rarely arises spontaneously. It requires a clear purpose and processes that align operations with this purpose. In other words, form follows function, and without a clear function to fulfill there isn’t a reference point that can be used to evaluate the form an organization needs to take (noun). As Wildland is pre-launch, it is a suitable time to be engaging in this analysis, for the success of the functions surrounding the protocol itself.

What is Wildland

This section outlines further context on what is Wildland, why it matters, and to whom.

At present, the term “Wildland” refers to a few things:

- A protocol (for personal “data dockers”) that is free to use and open source

- A marketplace for infrastructure and services around that protocol

- A team that supports the design and development of the protocol and marketplace, which may evolve into a DAO-type organizational structure in the future, called Wildland’s User-Defined Organization” (which incorporates the Wildland Build Fund).

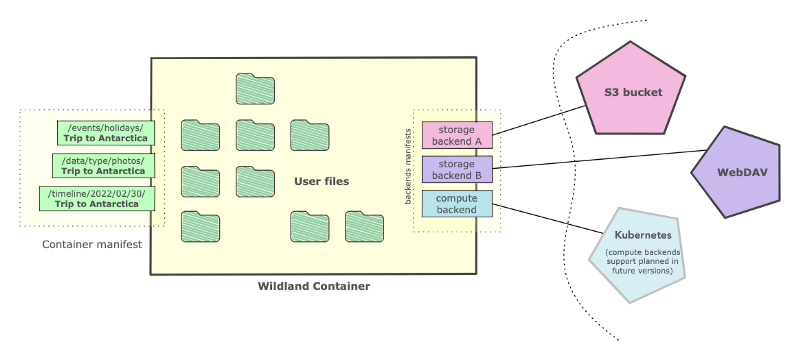

1. Wildland Protocol

- What: User-controlled data containers, infrastructure agnostic data storage, and curated chains of data (Memex trails / Wildland forests).

- Why: In a world where most data is “in the cloud” (on someone else’s server) the end-point (personal computer) is less and less important. To have control over data, users need to be able to create, verify, store, backup, move, and share data — quickly and easily — and in a way that minimizes dependence on trusted third parties. This is possible today, but it takes a lot of time and effort. Wildland aims to make it easier (default) so that data security, verification, and portability are accessible to more users.

- Who Cares: The initial target market for Wildland is individual end-users (a “business to customer” or B2C model). Users who create data pods can keep them private for personal use or choose to share read and/or write access with friends, collaborators, or even the broader public. Data pods can be linked together to create “forests” of data, and “trails” can be blazed through those forests by curating links of specific content related to a topic or interest. This is also possible with website and HTML links, but the current Wildland plan prioritizes user control through encryption and cryptographic signatures for data pod governance (whereas the current paradigm often prioritizes platform/server admins). With users in control, data becomes more portable, which makes infrastructure providers somewhat fungible (and thus less powerful). This aims to disrupt the current cloud storage market where a few entities have created walled gardens that give the platforms more control than end-users. If wildly successful, this has the potential to change the architecture of the web as we know it.

2. Wildland Marketplace

- What: Coordination system for users and service providers — initially cloud hosting services but potentially more in the future.

- Why: Users can run their own servers or rent space on someone else’s infrastructure. Setting up and managing your own server takes time and technical expertise, but using someone else’s infrastructure requires trust. This is the classic convenience/control tradeoff. This is not new to Wildland, but if the protocol makes it easy for users to backup and migrate their data, then switching costs between service providers could be minimized. If users have more control over their data via Wildland, then some of the risks of cloud hosting could be reduced while also increasing user convenience.

- Who Cares: If individuals like the idea of Wildland and want to try it out, but lack the resources (time, technical expertise, etc) to self-host, a hosted solution could be valuable to them. The easier it is for individual users to use Wildland, the more likely it is that they will create, share, and curate Wildland-based data. An easy-to-use Wildland hosting solution could support the emergence of a Wildland ecosystem.

3.a. Wildland Team

- What: Wildland is a project of the Golem Foundation, as per the whitepaper. Some folks from the Invisible Things Lab (ITL) (aka the QubesOS team) have been helping with prototyping the Wildland client as contractors. Wildland aims to create a user-centric infrastructure agnostic data management network.

- Why: The Invisible Things Lab has deep technical expertise in containerization and data management, and the Golem team has expertise in distributed computing. By combining resources (talent and capital), a distributed data network could synergize with the computing network. For example, you could have data pods that contain programs, and data pods that contain data, and you could use the Golem Network to compute the program over the data. Individuals or teams (DAOs) could create and maintain pods (data), and they could make them freely accessible to the public or charge a fee for access. If that data and programs were hashed, you could verify the exact data set and program version that was run, potentially helping to enable reproducible builds at scale. This would continue the research direction of ITL and potentially drive lots of usage of the Golem compute network, Wildland data marketplace, and the buying/burning of GLM.

- Who Cares: End-users who want control over their data. Developers who want to build new applications on Memex-style data architecture. GLM token holders who want more GLM to be bought and burned.

3.b. Wildland Build Fund

- What: A pot of capital to support the development of the Wildland marketplace, protocol, and ecosystem.

- Why: To bootstrap an innovation flywheel that supports the Wildland protocol, marketplace, and team/community, and remove dependencies on Golem Foundation so the project can be self-sustaining.

- Who Cares: The Wildland Team would like the Build Fund to be controlled by Wildland Marketplace users and to be the first team funded by the Build Fund to contribute to Wildland protocol and marketplace development. This way, support from Golem Foundation can dissolve and the ecosystem can be owned and operated by and for users. As Wildland is still at a proof-of-concept stage, the main initial stakeholders are likely to be development and research teams — rather than individual end-users. The current challenge is to bootstrap enough interest and engagement to build a working protocol and marketplace so that end users have something to use. This part is important because, as we’ll see, it’s hard to create user-defined organizations without any usage from users.

How do you transition from a centralized development team and funding process to a decentralized organization controlled by users if there are no users yet? We explore this question by looking at the proposed model of a UDO and provoking further thinking on the concept of “user” “defined” “organizations” from a first-principles standpoint.

The Current Proposed Model of a User Defined Organization (UDO)

Note: this is based on the current design as articulated on the Wildland blog, but it’s still in the early draft stage and is likely to change in the future.

Our current understanding, based on the Wildland blog, is that the Build Fund plans on issuing tokens to the users of the Wildland Marketplace, not the Wildland protocol. In this context “users” are users of Wildland Marketplace, not Wildland protocol users, and “usage” of the marketplace is understood as payments for services within that marketplace (referred to as “Proof-of Usage” (PoU)). The way this would work is that a portion of payments on the Wildland Marketplace would buy and burn GLM, and the address that paid for that transaction (proof of usage) and went through some sort of (unspecified) identity verification system (for Sybil resistance) would then get a “Proof of Usage” token representing usage of the Wildland Marketplace, and that token would be non-transferable (to prevent financialization), and it could be used to influence the governance of the Build Fund via quadratic voting (to prevent whale dominance). This means that the Wildland implementation of a UDO is directly connected to the Wildland Marketplace, but only indirectly connected to the Wildland protocol (which already has user-controlled data pod governance built into the protocol). In this sense, Proof of Usage is like a “play to earn” GameFi model but pay to earn (aka. a plutocracy). Earning usage tokens is tied to the usage of the marketplace, not usage of the protocol. Thus, users are paying for storage services in the marketplace to earn governance rights over a pile of capital (the Build Fund).

Based on this understanding, we have tried to identify potential concerns and limitations with the current Wildland ecosystem design, so they can be addressed in the design phase of UDOs and pre-launch of the Wildland marketplace. These are set out in the section that follows.

Limitations

There are multiple assumptions baked into this model, which leads to multiple concerns, based on both design concepts and attack vectors. The following section unpacks these.

Assumptions in the current UDO model include:

- There exists a usage measurement system and it is accurate (at present, this is proof of payment in the marketplace)

- There exists an identity verification and management solution and it is private and secure (Wildland plans on using an existing, Web3 DApp for this, such as BrightID)

- There exists a system to distribute tokens based on usage and identity and it is not easily game-able

- Tokens will be non-transferable to minimize any non-governance utility such as trading and speculation

- Token holders gain utility from governance and will want to participate in governance (e.g. write, read, debate, and decide on proposals)

- Combining multiple stakeholder classes (users, managers, owners) into one (token holder) will lead to the various outcomes described on the Wildland Blog

- Quadratic voting (QV) will minimize the influence of large token holders (who use the marketplace the most) and will give a voice to smaller token holders (who use the marketplace less), while also ensuring that influence over governance reflects the level of commitment users have to the project.

Concerns

Too Many Dependencies

Like many projects tackling product innovation and governance, solving numerous complex challenges, such as measurement, identity, user-centric governance, sustainable open-source financing, and capital allocation towards platform growth simultaneously is hard. The currently described UDO design is dependent on all of these challenges being solved, any one of which could undermine the entire system if it were compromised or faulty.

Clear Purpose

Throughout the Wildland blog posts, the purpose of an organization is discussed as if it is well defined, generally known, and broadly agreed upon. In complex organizations, none of these characteristics of a “purpose” can be taken for granted. This is because an organization’s animating purpose, in constituting the organization itself, defines the future institutional margins that different stakeholders’ divergent preferences and interests then vie within (Alston, et al., 2021). An organization’s constitutive purpose subsequently provides a means of assessing what is good faith action within the collective choice set of an organization. Absent clearly defined constraints on the expenditure of public funds, administrators can justify numerous kinds of spending, all arguably in furtherance of a poorly constrained “public purpose”. This makes a clearly articulated purpose of an organization and constraints on the collective choice process intended to further that purpose essential to aligning interests among diverse stakeholders within a given organization. With a sufficiently diverse group of stakeholders, it can be indefensibly reductive to label an organization as having a single agreed-upon purpose, for such a label for democratic governments likely does not exist singularly for all citizens. This emphasizes how all complex and durable organizations create a political economy containing stakeholders who are present for very different underlying reasons. Thus, references to purpose throughout can be taken to repeatedly emphasize the importance of this component of organizational design, as opposed to assuming that a well-defined and constrained purpose animating collective action emerges automatically.

Distribution of Power

The Wildland blog states that: “The central assumption behind UDO is that there should be a strict tie between the platform’s governance and its usage. Only those who use the platform should have decision-making authority over it, and their influence should reflect the level of their commitment to the project.”

If tokens are distributed based on usage, and those tokens are non-transferable, then those who use the marketplace the most will have the most influence over the Build Fund (Wildland’s UDO implementation). This is a stated design goal of PoU and the Wildland Marketplace UDO. At the same time, quadratic voting reduces (but does not eliminate) the outsized influence of those with the most power in a system because their voting weight is squared. But if in Wildland those with the most power are those who use the platform the most, and the goal is to give those who use the platform control over the platform, then composing PoU and QV could be in opposition to that goal.

If, however, the goal is to distribute power more evenly among all users, then that could disenfranchise those who have the most skin in the game (and are the most affected by the platform — aka power users) at the expense of less engaged and less incentivized users (the majority of more casual users). If the majority (of casual users) has power over the minority (of power users), but the majority is less informed, engaged, and exposed to the consequences of governance than the minority, that could create an incentive for the majority to extract value from the minority (high fees) or for the minority to try to influence the majority to get what they want (via lobbying or bribes).

User Motivation

The current design assumes that users want to be owners and actively participate in defining system parameters and resource allocation (with all the time, labor, and management responsibility that entails). Owning things often seems attractive until you have to put in the work to manage and maintain those things. Without incentives to invest time and effort into managing and operating a system, users are likely to get excited about the project initially, but then forget about it, choose not to put in the effort to contribute, or worse, just vote on popular ideas proposed by influential personalities (potentially with a reward attached) without understanding the context or likely outcomes of those decisions (because the cost of becoming informed is high, but the impact of voting — and thus the value of political information — is low). This tendency is potentially exacerbated by quadratic voting if smaller users’ incentives are only weakly implicated by any one decision, even if the aggregate or long-run implications of the decision are large.

User Choice

The Wildland blog states that: “If web3 is to deliver a real alternative to the current model of the internet where power accrues to investors and users are treated as bits in a revenue stream, then the governance modes of decentralized platforms should prioritize the users’ interest and provide them with effective “voice and exit” opportunities. The User-Defined Organization, or UDO for short, is Golem Foundation’s attempt at giving users actionable control over the protocols, software, and platforms they rely on.”

The current User Defined Organization design puts many constraints on user control and governance (token properties, token distribution, voting mechanisms, etc). This is a paradox because if an organization is defined by users, then you can’t define the organization until there are users, but if you define the organization a priori, then it’s not defined by users. For example, many of the ideas proposed by Wildland seem to assume that a system has a clear purpose so that you can constrain governance around that purpose. Yet, if an organization and its purpose are defined by users then you can’t pre-apply constraints. Yet, this is what the current design does (stating that PoU holders will determine the inner workings of the Wildland payment system, the parameters of PoU token generation, and UDO governance itself), without defining who the different classes of users are, what their goals might be, and how those might be aligned or misaligned.

A potential compromise might be creating a simple and minimal initial design for UDOs that involves setting initial parameters, that are then modular and upgradeable. This way, while initial conditions might be set from the top down, the organization could evolve over time (and be defined by users) from the bottom up. This comes with its own set of challenges pertaining to governance design, especially post-enactment (including defining the governance surface, managing stability and adaptivity, etc).

Non-transferability

The Wildland blog states that: “By tying governance with usage and making the governance token non-speculative we are ensuring that the UDO will be controlled by people with a skin-in-the-game interest in its future, and reducing the surface of economic attacks which can be successfully launched against it”.

To understand the consequences of this design goal, the governance experiment must be run.

If those with the most skin-in-the-game (power users) are disenfranchised then those with less information, experience, and incentives will have more power in the system. At the same time, minority users are likely to have less of an opinion on how that power is used because they use the system less and are less exposed to the consequences of its governance (aka. less skin in the game). If the value of governance for these users is low and if the effort required to gain and maintain an informed opinion about the system and various governance proposals is high, then users might be less likely to become informed independently (intrinsic motivation) and more likely to participate in governance because of lobbying or bribes (extrinsic motivation). In other words, information is costly, and people are unlikely to make that investment unless the expected rewards of doing so (intrinsic or extrinsic) are higher than the cost.

In short, if the expected rewards of political information and/or participation are negligible, people are unlikely to become informed and/or participate in the political process of governance (paraphrased from Michael Huemer).

Identity

The Wildland blog states that “During the app onboarding process, new users will be asked to prove their unique identity (without revealing any personal data) using an unobtrusive and privacy-respecting proof of uniqueness solution”.

From conversations with the team, we understand that Wildland intends to integrate an existing Decentralized Application to address uniqueness, rather than design their own. The caution here is that this is a very challenging component (for any project to solve, and as a component of any project).

Decentralized and privacy-preserving identity is an open challenge, mainly in part because there are so many ways it can be gamed — but also because after identity has been verified personally identifiable information (PII) needs to be securely stored and/or processed. Given the sensitive nature of the cryptocurrency space, and the global nature of its users (with various ‘real-world’ jurisdictions and legal constraints) a compromise of PII could have severe consequences. Beyond questioning the assumption that this is a required mechanism to achieve the systems’ design goals, there is an open question as to how such an identity verification and management system would work in practice — who and how would the data, data security, and storage would take place. The caution here is that assuming responsibility for incorporating a faulty identity system could be worse than not including one at all. As such, designers may wish to explore a design that is not dependent on identity.

Lobbying & Bribes

The Wildland blog states that: “Only those who actually use the platform should have decision-making authority over it, and their influence should reflect the level of their commitment to the project.”

If PoU token holders are publicly visible on Ethereum, and PoU token votes are verifiable on-chain, then anyone can airdrop tokens to addresses based on how they voted. Given the public permission-less nature of Ethereum, this can’t be stopped because it’s outside of the Wildland system. In short, anyone who wants to influence any group of public token holders can try to do so. As a result, the currently proposed identity verification internal to Wildland cannot affect public lobbying and incentives outside of Wildland (especially if actors are anonymous). If this were to happen, it’s difficult (if not impossible) to tell if a user voted for or against a proposal because they supported the proposal (intrinsic motivation) or because they wanted to receive a reward (extrinsic motivation).

Proposal Scope

The Wildland UDO design does not speak to the scope of governance proposals; or how resources from the Build Fund (as the first instantiation of a UDO) can be allocated. This lack of specification leaves the governance surface of the Build Fund UDO unbounded. For example, proposals broadly related to building the Wildland ecosystem could include, but are not limited to: developer team funding, ecosystem grants, app mining (direct subsidy for applications), usage mining (direct subsidy for marketplace end-users), acquisition of other protocols, integrations with other applications or platforms, migrations to new chains, and even pivot to new use cases and product offerings. We are not recommending or advising against any of these strategies, rather, we are pointing out that the proposal’s scope is unbounded. This creates an incentive to try to game the system to get more PoU tokens (or to influence current PoU token holders) to vote through Build Funds proposals that favor special interests. In short: the current design creates some of the incentives and dynamics of a public finance problem, and all the problems that entail but without constraining the scope of proposals for that public financing.

Who Governs the Wildland Marketplace Itself?

The Wildland blog states, “each payment made on this marketplace will be divided into three parts: the service fee, the Proof-of-Usage fee, and the build fee. The service fee, constituting the largest part of the whole payment, will go to the provider from whom the user has bought the storage.”

It is unclear who decides what those fee rates are (potentially Golem Foundation), what the role of users is in this definition (if any), and how users and service providers can be confident that the fees won’t change against their interests (for example to burn more GLM) in the future.

Beyond that, running a marketplace is a lot of work because there are a lot of variables to control. This includes, but is not limited to:

- Who gets to be a service provider, including:

- Can service providers be removed from the platform?

- If so, how does that moderation/governance process work? - How does service provider reputation work?

- Can this system be gamed to favor certain providers over others?

- Can this system be influenced by lobbying and bribes? - How are service providers featured on the marketplace?

- Could the platform operators favor certain providers over others, potentially because of out-of-system bribes?

- Could the Wildland developers favor the Wildland Foundation services over competing third parties (like Amazon does on their marketplace)? - What are the fees?

- How are those fees split between the service provider, GLM buys/burn, and the Build Fund?

In the current design, the Build Fund gets revenue from the marketplace. This creates an incentive to deploy capital to support the development of integrations and services within the marketplace — and even to subsidize the use of those services or the marketplace itself to drive more fees for the Build Fund. This is the classic marketplace startup model of subsidizing growth until network effects are reached and fees can be supported organically, and potentially even be raised over time. In short, the economic relationship between the Build Fund and the Wildland Marketplace creates an incentive to support initiatives that grow (and centralize) user activity in the Wildland Marketplace — and to then extract value from that activity over time (raising rates). This might not be the intention today, but the incentives are there. Empirical evidence has shown that over time systems with incentives to centralize tend to do so. While this cycle may benefit the marketplace, it could easily overshadow the Wildland protocol (think git vs GitHub).

Initial Conditions

The Wildland blog states: “Relying on a single source of funding can also result in a development process that reflects only the needs and ideas of the seed investors.”

The current design seems like it incentivizes using the Build Fund to invest resources to maximize Wildland Marketplace usage, and thus GLM burn, and this alignment of incentives seems biased towards the needs of the seed investors (Golem Foundation) at the cost of Wildland users (who might benefit from a more open, competitive, and diverse ecosystem not concentrated around the Build Fund and a single primary marketplace for services). We understand that the Golem Foundation has funded the project so far. The link to GLM in token design requires further investigation for a viable solution that promotes the overall security of the protocol, or as a non-negotiable system requirement.

Open Questions

The Wildland blog has a few open questions with regards to UDOs. We address them succinctly, as follows:

What should be the scope of the PoU-token holders’ agency (i.e. what issues are to be voted on besides the Build Fund management: the parameters of the PoU token generation process, the organization, and the inner workings of the UDO itself?)

As much as possible. If the organization is going to be “user-defined”, users need to be able to define it.

How do we ensure high PoU-token-holders turnout during polls? (DAOs, like most polities, experience low voter engagement, can we incentivize UDO participants to be more active in this regard?)

Becoming informed and participating in the political process of governance (writing, reading, discussing, and deciding on things) takes time. Time is a scarce resource. For people to expend scarce resources consistently there needs to be a return on that effort. There needs to be an incentive. The way the system is designed currently only a small subset of “users” (those that purchase services in the marketplace) are likely to be incentivized to participate in governance, but even if they do, their influence will be reduced by quadratic voting. This reduces the expected impact (return on effort) of governance participation. If the return on governance participation is low, people won’t remain engaged over time. If most people don’t have an incentive to care about governance, special interests who could benefit from certain proposals will likely engage with users (PoU token holders) in ways that maximally benefit them — such as lobbying and bribes (outside of the Wildland system), as detailed above. This would make it difficult to measure “good faith” voter turnout (intrinsic motivation) versus rent-seeking (extrinsic motivation). Comparatively, high voter turnout might otherwise reflect the level of rent-seeking possibilities a system has inadvertently created.

What’s the volume of market transactions which is necessary for the creation of a self-sustaining Build Fund?

This is dependent on the marketplace fee percentage and the burn rate required to sustain operations which cannot be known before there is a solid system design, target market, go-to-market plan, and so on.

How should payments made on Wildland’s marketplace be divided (i.e. what percentage of the payment should go to the provider, the Build Fund, and the PoU fee, respectively)?

Users could define this. For example, many DeFi systems have the option for fees, but it’s up to token holders to turn them on if they want to.

What are the vectors of possible economic attacks against the UDO?

The above points detail attack vectors on complexity, centralization, defining the boundaries of governance, identity, small game fallacies, and more.

Conclusion, Part 1

Wildland protocol presents a prospective new model for managing data storage in a distributed, user controlled manner. Meanwhile, the Build Fund User Defined Organization in its current design may be extremely difficult to implement given the dependencies on solutions to multiple complex problems. Even if built, the Build Fund UDO may enact incentive misalignment between a motivated minority to influence an apathetic majority.

This dynamic exchanges an incentive problem (making something people want and are willing to pay for) for a political problem (a community with aligned incentives and without collusion and compromise). This is done without actually solving the incentive problem that the community of users still needs to make something they want and are willing to pay for. Otherwise, the protocol and marketplace will run out of money to continue development and operations.

Beyond that, the Wildland platform is likely to have a diverse set of stakeholders with competing incentives, yet the system constrains how those stakeholders could acquire power as well as how that power could be used within the system to express and defend stakeholder interests. It’s not ‘user-defined,’ and as such, motivated stakeholders (users) who want to influence (define) how the system operates (organization) are likely to look outside the system for ways to influence it — bypassing all of the constraints created within the system. The current Wildland design seeks to constrain power, but public smart contract blockchains (such as Ethereum) were created to enable users to define their organizational structures and power dynamics through composable, permissionless smart contracts. Thus, they are likely to continue to do so. If stakeholders are likely to go outside the system to influence it, the system may be better off having fewer constraints to begin with, by operating from a first-principles model of initial settings of what a UDO could be.

Rather than trying to constrain power, the Wildland UDO system (as separate from the use of the Wildland protocol itself) may progress by keeping things simple and aligning incentives. Simple, stable, governance minimized foundational settings could allow users to create and define their own organizational and incentive structures on top. This could support an emergent ecosystem that is bottom-up and user-defined, rather than an imposed system of governance that is top-down.

By working with the nature of composability by keeping systems small and simple, the power of public blockchains can be leveraged to support an emergent governance structure. The value add of computer-aided governance tools, such as permissionless protocols, is to align incentives and maximize user choice within clear boundaries, for a public, permissionless organizing environment that does not try to constrain user choice.

With this goal in mind, the recommended next step is to ‘separate the forest from the trees’ by exploring what a first-principles approach to “User Defined Organization” might look like. This piece comprises the first step in analyzing and developing the concept of a “User Defined Organization”.

We are enthusiastic about the prospects of Wildland protocol itself to change how data is owned and managed on the internet and to continue to explore how users may be able to define and accrue value in conjunction with this system.

In Part 2 of the research, “Applying Lessons from Constitutional Public Finance to Token System Design,” we analyze the concept of “Proof of Usage” from the perspective of constitutional public finance, toward the goal of user-defined, democratic ordering of public finances.

This report was authored by members of the BlockScience Governance Research Team: Burrrata, Kelsie Nabben, Eric Alston & Michael Zargham. With special thanks and appreciation to the Golem Foundation, Wildland team, and the BlockScience team for feedback, including Jessica Zartler for suggested edits.