By Kelsie Nabben (RMIT / BlockScience), Michael Zargham (BlockScience), & Ellie Rennie (RMIT University)

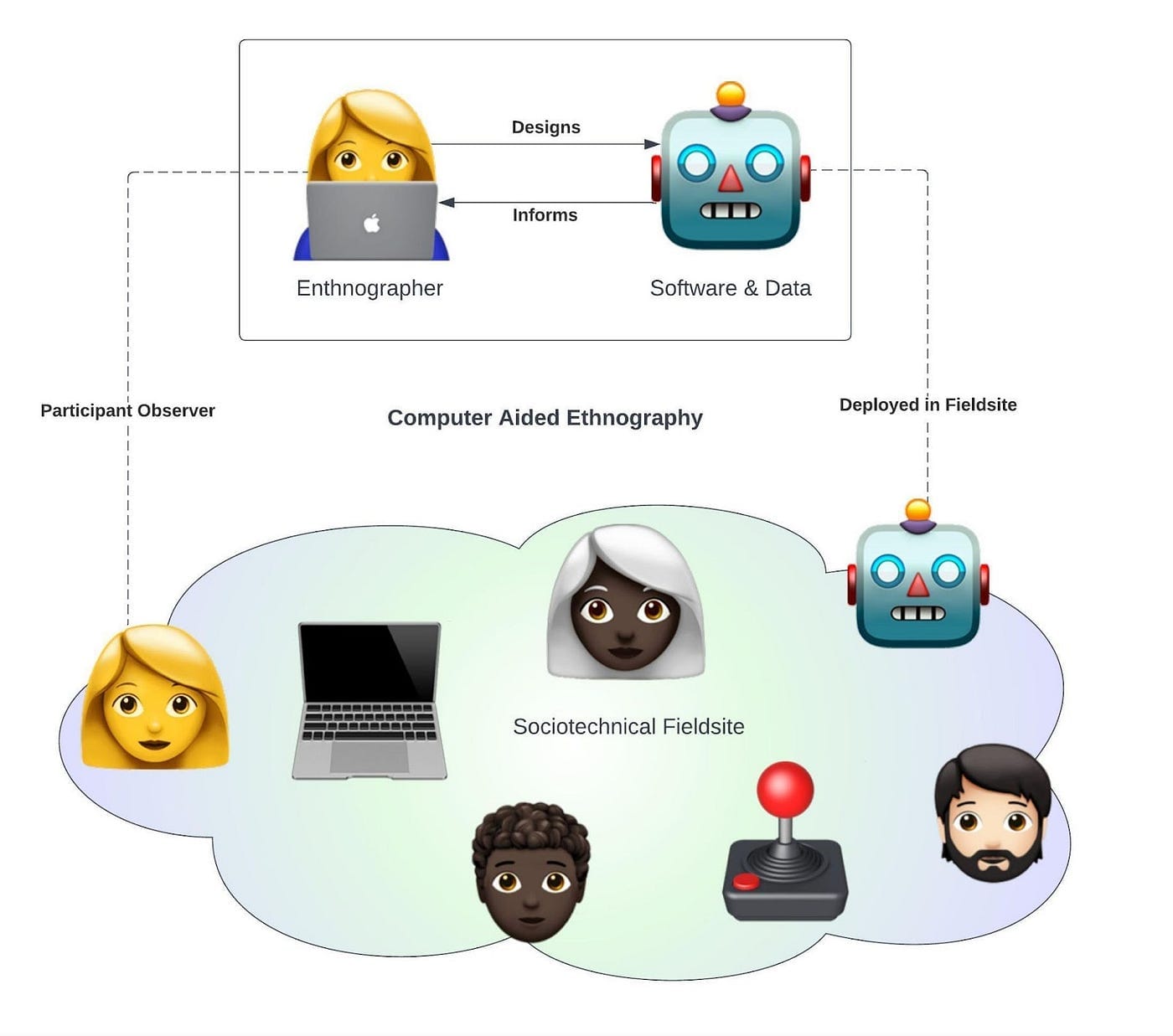

This post discusses a concept which builds on existing ethnographic approaches, that we call ‘Computer-Aided Ethnography’ (CAE). Our ethnographic research on Web3 uses some of the same software tools that define ‘Web3’ (referring to communities that participate in the practice of decentralized technologies, such as public blockchains), as digitally native communities. In this post, we discuss why we do this, as well as how it builds on existing practices of ethnography to enable participation by a community being researched on their own terms. We find that CAE offers a unique methodological approach that enables research participants to contribute to both the social and technical dimensions of the research according to their preferences, creating fertile ground for ethnographic interactions and co-constitution in the field of Web3. It remains to be researched how CAE methods may be adapted and applied in other digitally native field sites.

Introduction

A community that assembles and uses digital tools becomes more-than-human when these tools are essential to that community’s operation. For instance, a decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO) may use smart contracts for actioning the decisions of members who wish to remain pseudonymous (for more on what is a DAO, see Nabben and Zargham, 2022). These actions would otherwise be difficult (if not impossible) as other options for minimising risk would require information about members that they are not willing to share. For such communities, peer-to-peer Web3 technologies are not just tools, they are machine agents that the community intentionally deploys to manage what members can and can not do. Not only do they define some important boundaries and intentions of that community, in most cases the community would not exist if not for these tools. As researchers using ethnographic methods, we have been utilising some of the same tools and infrastructures in our research, in conjunction with these communities. We do this to define the “field” within which our work takes place and to enable participation by the community on its own terms. We call this approach Computer-Aided Ethnography (CAE), which is a subset of the broader practice of digital ethnography.

Where CAE comes from

Ethnography is traditionally a qualitative, inductive methodology with origins in cultural anthropology that relies on first-hand experience to gather observational and interview data and produce detailed and comprehensive accounts of different social phenomena (Hammersley, 2006). Ethnography is widely used to investigate people’s lived experiences in and across cultures and communities.

The concept of ‘Computer-Aided Governance’ (CAG) refers to how we can use computers and computational innovations to better understand and steer complex systems, and emerges from complex system research and development firm ‘BlockScience’ (Zargham & Emmett, 2019). For example, CAG can provide tools and techniques for people to design and analyse governance proposals for complex, sociotechnical systems (Burrrata, 2021).

As an extension of this approach, CAE is about how we can use computers to better understand and research the dynamics of complex systems that incorporate digital components. In the same way that CAG is not governance by computers, CAE is not research by technology but rather research that leverages the technologies of the field being studied, to integrate the researcher into the practices of the communities they research.

For example, Computer-Aided Ethnography is a valuable tool in the ethnography of decentralised technology communities (or “Web3”) because this is a sociotechnical field-site, composed of both social and technical dynamics (Nabben & Zargham, 2022). In this context, qualitative methods offer insights into the novel modes of self-governance occurring but technical tools are required to navigate the field-site and complement the researcher and/or participants.

How CAE fits within existing ethnographic methods

Computer-Aided Ethnography is a subset of existing digital ethnographic methods. Ethnographic methods that acknowledge the relevance of digital environments are not new. Hine pioneered the methodology of “virtual ethnography” that considers “the field” in various forms, encompassing online and offline environments that have become embedded within our everyday lives and change culture, including the internet, new platforms, and devices (2000). Sherry Turkle and others have then broadened the focus of sociology to inspect the implications of ‘the digital’ through a focus on technological transformations that accompany ‘the digital age’ (Robinson & Halle, 2002; Turkle, 2005; Turkle, 2011).

Furthermore, digital ethnography is less a specific method, and rather an approach to doing ethnography in the digital world that acknowledges both the study of the consequences of digital media in the everyday on people, culture, and society, as well as ways in which the practice of ethnography can occur through various forms of digital media (Pink, et. al., 2015). Digital ethnography encompasses “studies of people, societies, and sociotechnical relations that are digitally-saturated, or somehow impacted by transformations wrought by digitalization, widespread internet connectivity, and the largescale datafication of society” (Markham, 2016). Pink, et. al. describe the principles for digital ethnography as multiplicity, non digital-centricness, openness, reflexivity, and unorthodox (2015). Thus, digital ethnography embraces digitally mediated contact with research participants, as well as other digital information which offers an insight into human behaviours and expression, including data produced by humans, such as public-blockchain transaction records, social media ‘bios’ or interactions, and other movements or flows of information and value. Within such studies, knowledge is derived from investigation, observation, experiment, or experience. Another approach in this vein is netnography, a qualitative research method concerned with the study of online cultures and communities, especially through and about social media networks (Kozinets, 2006).

Researchers have also explored the application of computational methods in the context of ethnography. Computational ethnography (or ‘computational anthropology’) extends ethnography’s qualitative methodological toolkit with computational methods by conducting mixed-method scholarship in line with the broader principles of ethnography (Brooker, 2022). The logic here is that “our methods of knowing the social world should come from those whose day-to-day life produces it, rather than imposing a framework” (Brooker, 2022). Some examples of this practice exist, focusing on the practice of data science to support ethnographic methods (referred to by some as ‘trace ethnography’) (Geiger & Ribes, 2011; Geiger, et. al., 2018). Computational ethnography is also referred to as unobtrusive automation of data collection in situ (Zheng, et. al., 2015), and a way or addressing ethnography’s weaknesses (e.g. limitations in sample size and analytical transparency) by helping to scale ethnography, improve transparency, and address validity concerns, through techniques such as data visualisation, Social Network Analysis, and textual analysis (Ambramson, 2018). Yet, computational ethnography remains underdefined and underdeveloped as a comprehensive methodological approach. Thus, in our ethnographic practices we have been developing and applying ‘computational ethnography’ methods in the field of Web3 in novel ways, which will be explained in more detail below.

Furthermore, computational social science has also explored using data and computational tools to explore social science topics, closing the divide between the two disciplines (Ledford, 2020). Here, scholars have previously suggested ways to utilise digital tools to study digital domains, such as the Web. For example, based on the claim that the Web is a knowledge culture distinct from other media, Richard Rogers concentrates on the research methods and tools that would have not been possible without the Internet, that also align with the cultures of the Web (Rogers, 2013). Web native tools in research include building and tracking URL lists to identify censorship, making Twitter APIs comprehensible, researching Instagram hashtags, and documenting and analysing Facebook media (Rogers, 2019). Other scholars have explored how computational methods apply to social science practices, such as historical analysis but with an emphasis on developing technical skills, such as learning how to code (Brügger, et. al., 2019; Ledford, 2020). This approach does not necessarily encourage multi-disciplinary collaborations between computational and social scientists, as well as not necessarily imbibing the technical culture of a community being studied.

Rather than a reappropriation of ethnography in new (digital) settings, CAE is a necessary extension of traditional ethnographic methods. In contrast to the prior approaches outlined that Computer-Aided Ethnography seeks to build upon, Computer-Aided Ethnography is not about using computational tools to extend traditional ethnographic methods or teach social scientists to use technical skills and tools. Rather, it uses and extends the computational tools of communities that have a presence in digital spaces. In this respect it follows participatory approaches pioneered in the fields of participatory communication and citizens’ media studies that bring community members and their chosen medium into the processes of data collection and sense-making (Cornish & Dunn, 2009; Tacchi, 2015). The remainder of this post explains CAE in more detail, including core principles and examples.

Both the introduction of novel or adapted technical components (e.g. software) and the ethnographer’s presence as a participant observer modifies the sociotechnical field-site. The phrase ‘sociotechnical’ here refers to the interrelatedness of social and technical aspects of a system, describing the complex interplay between people and technology in which neither the social (such as people, relationships, and structures), nor the technology (such as hardware, software, and processes), can be considered in isolation from one another (Golden, 2013; Nabben & Zargham, 2022). This increases the fidelity of the observations through a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection and triangulation of findings, while also increasing the direct impacts the ethnographic practice has on the field-site. Introducing technical tools to the field-site can also make it harder to distinguish phenomena created by the introduced tools from those already present, especially as the tools being introduced in CAE are digitally native to the community but adopted, and possibly adapted, by the researcher/s.

The Principles of Computer-Aided Ethnography

Through our practice, we have found that the dominant conceptions of digital ethnography as a method of digitally mediated contact and digital information as data only get us so far in understanding the principles and practices of communities that reside in digital spaces, and engaging with them. Computer-Aided Ethnography utilises the digital tools of the community being studied, both to enhance research methods and deepen ethnographic experiences and insights, whereby computational tools augment research practices of observation, participation, data collection, data analysis, and findings communication and dissemination. CAE does not only acknowledge people’s occupation of digital spheres but utilises computational tools to enhance qualitative research practices.

Thus, CAE uses digital-ethnographic methods not only to observe online communities but to access, understand, engage with, and process the subtleties and dynamics of communities that interact in digital spaces. This methodological approach is especially relevant for field sites such as Web3 communities where the practice of self-governance includes (but is not limited to) digital self-infrastructuring (Nabben, 2022). Thus, it is possible in other digital domains but this is context and culture dependent.

CAE is not digital centric but digitally curious. As such, the method utilises existing tools of the community being studied and innovates new tools and techniques that integrate human-machine collaboration throughout the research lifecycle, according to the guiding principle that technical mechanisms augment the researcher and research participants.

1. Leverage the digital tools and infrastructures that research participants use

This component of CAE pertains to access, which refers to the process of entering a field site, or in this case, entering a digital community and culture. By using the tools of the community being researched in novel and relevant ways that enhance the research practices, processes, and/or findings, the researcher enters the field site to become a participant-observer. This makes the ethnographer a social element of the sociotechnical system being studied and potentially a technical element of the system, depending on if they participate in operating infrastructure, such as running a node in a peer-to-peer network. For example, in decentralised technology communities, this may include Discord (Web2 chat application), public blockchains, Twitter, data content and storage networks (e.g. IPFS and Filecoin), multi-signature wallets, etc.

2. Identify (or develop) tools relevant to the digital field site to augment research practices through community participation

This component of CAE pertains to conducting research (observation and data collection) in a digital-first setting. CAE integrates computational methods into research practices, including data collection, data management, and data analysis. This is predicated on consent of, and benefit to, the humans in the system being studied. As such, CAE rests on the assumption that computers can augment human behaviours, including research practices. For example, a community using the chat applications ‘Telegram’ or ‘Discord’ may choose to introduce software “bots” to tag and log data, provide access to channels, or answer questions (Rennie, et. al., 2022).

The ethical considerations of introducing tools to a field-site must be considered by the researcher/s before commencing CAE. In this regard, Web3 communities are viable candidates for Computer-Aided Ethnography because they are already engaged in experimental self-infrastructuring and have a bias in favour of the introduction of technical mechanisms to their communities (Nabben, 2022). CAE is not exclusive in its applicability to Web3, but Web3 is culturally relevant and appropriate to methods that surface the need for a methodological approach that leverages the digitally-native and participatory nature of this field.

3. Reflexivity on social and technological experiences and adaptations (“Techno-reflexivity”)

This element of CAE emphasises the importance of reflexivity, and how it changes in CAE settings. Ethnography introduces the role of the researcher as a “participant observer” in the field, with the positionality of the researcher adding a social element to the dynamics we study. When we study sociotechnical systems with CAE, we can go one step beyond being participant observers by also leveraging pre-existing computational elements from the community being researched in the field, or introduce culturally appropriate computational elements as new actors in the field in which research participants participate, adding a technical element to the sociotechnical dynamics we study. As such, we must practise techno-reflexivity (as the positionality of the technology we introduce, not just our own positionality as researchers (Nabben & Zargham, 2020)), because we are acting as both participant observer and as “infrastructurers” (designers, builders, and operators of infrastructure (Nabben, 2022)) when we introduce new technological elements into the fieldsite.

Reflexivity is a process of reflection involving both emotion and cognition that results in new understandings of a phenomenon (Boud, 2010). Through this tool in ethnography, researchers engage in explicit, self-aware analysis of their own role and how intersubjective elements influence data collection and analysis (Finlay, 2002). In CAE, reflexivity must be practised with regards to both the social elements introduced (i.e. the participant observer/s) and the technical elements introduced (any technical tools the researcher/s adopted, adapted, or introduced). This practice of reflexivity in contexts where technology is subjectively designed or utilised by software developers or researchers can be referred to as “techno-reflexivity” (Nabben & Zargham, 2020). Relevant questions for the researcher/s to reflect on include; what is the cultural exchange when conducting CAE / between ethnographers and the community? What changes did the presence of the researcher/s, and/or their technical introductions create to the field site? Was any effect of the field social, cultural, or technical? And so on.

4. Utilise the digital tools and infrastructures that the research participants use to communicate and disseminate research findings

This aspect of CAE is about the communication of research insights and findings. It requires the researcher/s to identify, observe, acknowledge, and leverage the cultural and communication practices of the community being studied. Digital communities often have unique communication methods and styles (Coleman, 2009). In order for researchers to effectively communicate and disseminate research findings in the ‘attention economy’ of digital spheres, researchers must leverage digitally native and culturally relevant approaches, tools, and platforms (Nabben & Zargham, forthcoming). An example of this in decentralised technology communities is the concept of ‘open-sourcing’ initial research insights as they arise, to align with the cultural norm of developers making software code publicly available for engagement (or ‘open source’).

CAE leans into and proactively seeks benefits to the researcher and research participants from introducing software (or other infrastructure, including hardware) into the field site, while being aware enough to safeguard against its harms, and also accounting for its own impacts on the system being studied.

An example of this is seen in the research project and paper that introduced an application extension bot called ‘Telescope’ to a community’s Discord chat application to help the community work with the researchers to identify and tag relevant research data in the chat (Rennie, et. al, 2022). The Telescope is a means to ensure that participants have visibility over the data that is being used and a means to consent (or not) to their dialogue being quoted in the research. It also involves community members in the process of data collection and reveals to the researcher the things they consider to be significant. Developing, deploying, and iterating on the Telescope Discord bot requires awareness and reflexivity on how introducing a novel computational research element affects and changes the dynamics of the community being observed. When the Telescope is active in a Discord server the approved comments appear in a bridge channel. We found that visibility over approved comments can prompt further discussion among community members, including dialogue on why themes and posts are significant (Rennie, et. al, 2022). In our next use of this tool we are experimenting with how the same dynamics might occur across DAOs using the same bridge channel (via the ‘DAODAO’ DAO). While ethnographers have long debated their role and impact in the field (for instance Altman & Hinkson 2010; Adler & Adler 1987), in this case the research tools are also extending the technical domain of the DAOs we study.

Conclusion

This piece has explored the methodological concept of “Computer-Aided Ethnography”, as a type of digital ethnography that enables participation by a community being researched on their own terms, which includes being able to participate in both the social and technical dimensions of the research. CAE is about what computational methods in qualitative research in Web3 domains (and potentially other digital domains) allow, as well as conducting research in a way that aligns with the culture of the community being studied in digitally-native domains. As such, CAE integrates qualitative and quantitative approaches to offer a unique approach to the investigation of digitally native communities, such as Web3. In setting out the core principles of CAE and providing examples of how this method is being practised in various contexts (see list that follows), our aim is to push the frontiers of doing digital ethnography in relevant and interesting ways to the communities we research, and enabling avenues of participation in ways that suit the preferences for engagement of these communities.

Examples of Computer-Aided Ethnography in Practice

The following is a list of research projects at the forefront on decentralised governance, that are pioneering and utilising CAE methods to surface research insights and findings. This work is just some that we are aware of, coming out of BlockScience, RMIT University, Metagov, and others.

Nabben, K., and Zargham, M. (2022). “The Ethnography of a ‘Decentralized Autonomous Organization’ (DAO): De-mystifying algorithmic systems”. EPIC Conference Proceedings, ‘Resilience’, 2022. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/epic.12104.

Rennie, E., Zargham, M., Tan, J., Miller, L., Abbott, J., Nabben, K., & De Filippi, P. (2022). Toward a Participatory Digital Ethnography of Blockchain Governance. Qualitative Inquiry, 10778004221097056.

Rennie, E. 2020. “The Governance of Degenerates Par II: Into the Liquidityborg”. Medium (blog). Available online: https://ellierennie.medium.com/the-governance-of-degenerates-part-ii-into-the-liquidityborg-463889fc4d82. Accessed Dec. 2022.

Tan, J. Z., & Miller, L. V. (2022). Building Net-Native Agreement Systems. MIT Computational Law Report. Available online: https://law.mit.edu/pub/buildingnetnativeagreementsystems. Accessed December, 2022.

Burrrata. “Mapping the Computer-Aided Governance Process.” BlockScience (blog), August 6, 2021. https://medium.com/block-science/mapping-the-computer-aided-governance-process-2e47eaf70889.

References

Abramson, C. M., Joslyn, J., Rendle, K. A., Garrett, S. B., & Dohan, D. (2018). The promises of computational ethnography: Improving transparency, replicability, and validity for realist approaches to ethnographic analysis. Ethnography, 19(2), 254–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138117725340

Adler, P., & Adler, P. (1987). Membership Roles in Field Research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984973

Altman, J. C., & Hinkson, M. (2010). Culture crisis: Anthropology and politics in Aboriginal Australia. University of New South Wales Press.

Boud, D. 2010. “Relocating Reflection in the Context of Practice” in H. Bradbury, N. Frost, & S. Kilminster (Eds.), Beyond Reflective Practice. (New York: Routledge). pp. 25–36.

Brooker, P. (2022). Computational ethnography: A view from sociology. Big Data & Society, 9(1). https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/10.1177/20539517211069892.

Burrrata. “Mapping the Computer-Aided Governance Process.” BlockScience (blog), August 6, 2021. https://medium.com/block-science/mapping-the-computer-aided-governance-process-2e47eaf70889.

Coleman, G. 2009. “CODE IS SPEECH: Legal Tinkering, Expertise, and Protest among Free and Open Source Software Developers.” Cultural Anthropology 24 (3): 420–54. DOI: 10.1111/j.1548–1360.2009.01036.x.

Cornish, L., & Dunn, A. (2009). Creating knowledge for action: The case for participatory communication in research. Development in Practice, 19(4–5), 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520902866330

Geiger, R. Stuart and David Ribes (2011). “Trace Ethnography: Following Coordination through Documentary Practices.” In Proceedings of the 44th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). http://www.stuartgeiger.com/trace-ethnography-hicss-geiger-ribes.pdf

Geiger, R.S., Varoquaux, N., Mazel-Cabasse, C., and Holdgraf, C. (2018). ”The Types, Roles, and Practices of Documentation in Data Analytics Open Source Software Libraries: A Collaborative Ethnography of Documentation Work.” Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (JCSCW), 27(3). DOI:10.1007/s10606–018–9333–1 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10606-018-9333-1

Finlay L. “Outing” the Researcher: The Provenance, Process, and Practice of Reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research. 2002;12(4):531–545. doi:10.1177/104973202129120052.

Golden, TD. 2013. “Sociotechnical Theory, in: Encyclopedia of Management Theory”. SAGE Publications, Ltd., Thousand Oaks. 752–755. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452276090.

Hammersley, M. “Ethnography: Problems and Prospects.” Ethnography and Education 1, no. 1 (2006): 3–14. doi: 10.1080/17457820500512697.

Hine, C. Virtual Ethnography (SAGE Publications Ltd: 2000).

Kozinets, R.V., 2006. Netnography. Handbook of qualitative research methods in marketing, pp.129–142.

Ledford, H. “How Facebook, Twitter and Other Data Troves Are Revolutionizing Social Science.” Nature 582, no. 7812 (June 17, 2020): 328–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01747-1.

Markham, A.N. “Ethnography in the digital internet era.” Denzin NK & Lincoln YS, Sage handbook of qualitative research, Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (2016): 650–668.

Nabben, K. 2022. ‘Decentralised Technologies as Self-Infrastructuring’. Mirror.xyz (blog). Available online: https://kelsiemvn.mirror.xyz/Obs11rquCCp20XB1nUiMTBU7bKWslThbfpF4Hf7n7Rg

Nabben, K., and Zargham, M. 2020. “Techno-reflexivity”. Substack (blog). Available online: https://kelsienabben.substack.com/p/techno-reflexivity-cf1331278bdc

Nabben, K., and Zargham, M. 2022. “The Ethnography of a ‘Decentralized Autonomous Organization’ (DAO): De-mystifying algorithmic systems”. EPIC Conference Proceedings, ‘Resilience’, 2022. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/epic.12104.

Brügger, N., I. Milligan, A. Ben-David, S. Gebeil, F. Nanni, R. Rogers, W. J. Turkel, M. S. Weber, and P. Webster. “Internet Histories and Computational Methods: A ‘Round-Doc’ Discussion.” Internet Histories 3, no. 3–4 (October 2, 2019): 202–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2019.1639352.

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., Tacchi, J., Digital Ethnography, London, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015.

Rennie, E., Zargham, M., Tan, J., Miller, L., Abbott, J., Nabben, K., & De Filippi, P. (2022). Toward a Participatory Digital Ethnography of Blockchain Governance. Qualitative Inquiry, 10778004221097056.

Robinson, L., and Halle, D. “Digitization, the Internet, and the Arts: eBay, Napster, SAG, and e-Books.” Qualitative Sociology, 25(3), 2002, 359–383. doi: 10.1023/A:1016034013716; Robinson, L. “The cyberself: the self-ing project goes online, symbolic interaction in the digital age.” New Media & Society, 9(1), 2007, 93–110. doi: 10.1177/1461444807072216.

Rogers, R. Digital Methods. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=82535a0e-75aa-48f8-8583-5aac0c9b900f.

Rogers, R. Doing Digital Methods. Los Angeles: Sage, 2019. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=b6d2bfa8-e75e-45d8-b34c-617db7a5914b.

Tacchi, J. (2015). Ethnographic action research: Media, information and communicative ecologies for development initiatives. In The Sage Handbook of Action Research (pp. 220–229). Sage.

Turkle, S., “Computer Games as Evocative Objects: From Projective Screens to Relational Artifacts.” In Handbook of Computer Game Studies, Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein (eds.), MIT Press, 2005.

Turkle, S., Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other

New York: Basic Books, January 2011.

Zargham, M. & Emmett, Jeff. “Computer-Aided Governance (CAG) — A Revolution in Automated Decision-Support Systems.” BlockScience (blog), May 19, 2021. https://medium.com/block-science/computer-aided-governance-cag-a-revolution-in-automated-decision-support-systems-9faa009e57a2.

Zheng, K., Hanauer, D. A., Weibel, N., & Agha, Z. 2015. “Computational ethnography: automated and unobtrusive means for collecting data in situ for human–computer interaction evaluation studies”. In Cognitive informatics for biomedicine. Springer, Cham. Pp. 111–140.