Online Governance Surfaces & Attention Economies

As decision rights expand, leaders face a new constraint: limited human attention. Even when participatory governance is possible, attention becomes the bottleneck. The paradox is clear — as organizations invite more people into decision-making, they risk governance overload that discourages the very participation they aim to promote.

In this seminar, Professor Nathan Schneider, Researcher Ronen Tamari, and BlockScience's Chief Engineer, Dr. Michael Zargham, discuss a co-authored paper on attention management as the critical bottleneck in digital governance systems, with direct implications for operational resilience in high-stakes environments. They share heuristics and principles to help design governance systems that allocate finite human attention efficiently to maintain trust, cohesion, and responsiveness.

Watch Video

Timestamps

Click to navigate to timestamps in the video

Part I: Foundations & Framework

- 00:00:00 Authors' Acknowledgment

- 00:00:30 The Problem of Governance Overload

- 00:02:01 Attention Economies and The Commons

- 00:04:58 Mapping Information & Decision Flows

- 00:06:46 Attention: Scarcity & Abundance

- 00:08:00 Risk Assessment: Attention as Labor

Part II: Case Studies in Web 3.0 Governance

- 00:08:29 Case Studies in Web 3.0 Governance

- 00:09:31 DAOstack & The Decentralized Governance Scalability Problem

- 00:12:32 Gitcoin: Liquid Democracy & Stewards Council

- 00:13:49 Governatooorr: AI Voting Agents & Automated DAO voting

- 00:15:05 Case Study Observations

Part III: Design Heuristics & Principles

- 00:17:54 Five Heuristics for Governance Design

- 00:20:29 Attention: A Critical Element of Governance Design

Part IV: Q&A Session

- 00:22:34 Shout Out! Digital Ethnographer Kelsie Nabben

- 00:23:28 Q & A: Representative vs. Direct Democracy

- 00:24:45 Q & A: Simultaneous Temporal Modes

- 00:26:54 A: Interoperable Systems Attention

- 00:27:37 Q & A: Incentivizing Governance Participation

- 00:29:48 A: Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation Trade-offs

- 00:32:33 Q & A: Governance Psychological Motivation

Executive Summary

Expanding participation does not always build stronger governance. When too many decisions compete for limited attention, organizations hit a ceiling: governance overload that erodes focus, engagement, and accountability.

As organizations pursue stakeholder engagement and distributed decision models, they risk replicating patterns observed in Web 3.0 organizations. This research discussion demonstrates that three common interventions — algorithmic filtering, delegation hierarchies, and AI-assisted decision-making — do not eliminate governance "attention" burden; they merely relocate it.

Key Insights:

- Attention as Infrastructure Risk: Treating governance participation as voluntary creates brittle systems. Organizations that under-provision attention resources—through inadequate training, unclear decision rights, or misaligned incentives— may experience governance failure often disguised as stakeholder apathy. In regulated environments, this can translate to compliance gaps and board liability. The research suggests that effective governance systems must explicitly provision for attention.

- Representative Democracy Reemergence: Web 3.0 case studies indicate that even radically decentralized systems return to representative structures when faced with complexity. Rather than resist this pattern, high-reliability organizations should design explicit "attention economics"— calculating governance load, setting participation thresholds, and creating tiered engagement models before deploying participatory frameworks. The research suggests that effective governance systems design information flows for heterogeneous engagement levels.

- Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Incentives: Financial mechanisms (fees, penalties, token rewards) demonstrably crowd out social motivations for governance participation. Organizations relying on gamification or compensation to drive engagement risk creating transactional cultures. The research suggests that effective governance systems must account for trade-offs between intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation.

- Unavoidable Trade-Offs: Organizations face a fundamental trade-off between governance legitimacy (broad participation signals inclusivity) and governance efficacy (concentrated expertise enables rapid response). Leaders must decide which governance surfaces to centralize in favor of focused expertise and speed, versus which to distribute in favor of broader representation. These design decisions must be recorded in a manner that makes these trade-offs explicit, measurable, and open to future reconsideration. The research suggests governance design must prioritize legibility and information design to lower the attention cost for busy participants to maintain confidence in the system without full engagement.

Preprint Research (2025)

This post represents an ongoing synthesis of BlockScience x Metagov collaborative research efforts, reflecting our intention to 'work in public' and share findings with a broader community audience. The following research is the basis for this Metagov community seminar.

Abstract

This paper considers the intersection of governance and attention in digital contexts. In particular, it argues for the relevance of ‘attention economies’, or the analysis of human attention as a resource, to ‘governance surfaces’, or the means available for organizational adaptation and action. Existing theoretical frameworks for the governance of community-managed resources lack adequate consideration for how people’s attention is engaged and directed. To address this gap, this paper proposes heuristics that assess how attention relates to governance in online organizations. The heuristics are informed by literature on attention economies and governance, as well as three case studies that consider recent attempts to address attention in the design of governance surfaces in blockchain-based systems. The resulting heuristics serve as analytical and normative tools to enable researchers and system designers to better understand attention in a governance system. They invite consideration of whether the structure of attention in a system is appropriate, efficient, and just.

This post was produced with the assistance of AI, as part of a broader inquiry into the roles that such systems can play in synthesis and sense-making when they are wielded as tools, rather than as oracles. Based on a Metagov research seminar, this post shares an edited version of the video, an adapted transcript, presentation slides, and research links. The original transcript was generated using Descript and reviewed by humans-in-the-loop.

Video Transcript, Presentation Slides & Associated Resources

Part I: Foundations & Framework

The Problem of Governance Overload | Attention Economies & The Commons | Mapping Information & Decision Flows | Attention Scarcity & Abundance | Risk Assessment: Attention as Labour

Part II: Case Studies in Web 3.0 Governance

DAOstack | Gitcoin | Governatooorr | Case Study Observations

Part III: Design Heuristics & Principles

Five Heuristics for Governance Design | Attention: A Critical Element of Governance Design

Part IV: Q & A Session

Representative vs. Direct Democracy | Simultaneous Temporal Modes | Interoperable Systems Attention | Incentivizing Governance Participation

Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation Trade-offs | Governance Psychological Motivation

Part I: Foundations & Framework

[00:00:00] Schneider: We are going to share a paper that this group of us in Metagov has been working on for a while now. The three of us - me, Nathan [Schneider], Ronen [Tamari], and [Michael] Zargham will present. But I also just want to acknowledge that our fourth co-author, Kelsie Nabben, is just not here because of time zone issues. But she is very much here in spirit and in her intellectual contributions to the work that we are sharing. Please imagine her in this space.

The Problem of Governance Overload

[00:00:30] Schneider: The problem we are taking on is in some sense a profoundly real problem and in some sense a kind of speculative problem. The speculative side of it is what happens if we win, which is to say what happens if we get governable, democratic inputs into our online lives everywhere we go.

What would it mean if the daycare you dropped your kids off at, the neighborhood you live in, the workplace you work in, the social networks that you are interacting with, and the online retailer that you are working with were all in some way co-governed by their participants, by you? Is that not in some sense tremendously overwhelming?

In many respects, this is something that has already come up as a problem for people trying to build self-governing online spaces. Many of the early experiments with Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) and blockchains encountered this question of what is the attention economy for governance? And we found that this question has not really been taken up in a serious way and theorized.

Attention Economies & The Commons

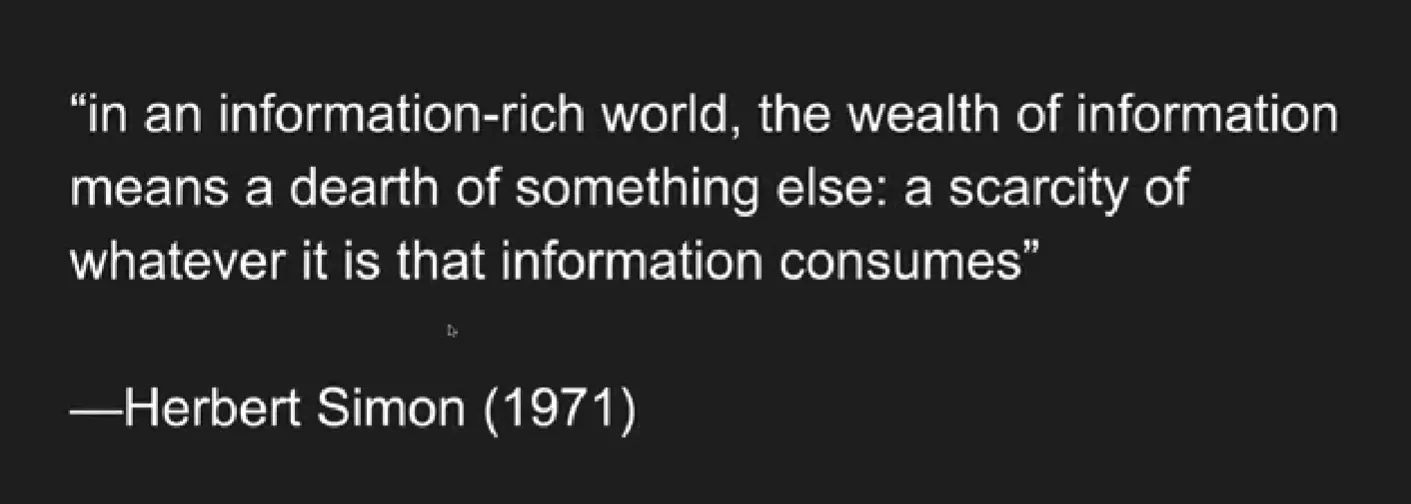

[00:02:01] Tamari: We started from this point of attention economies and how it has been theorized in the earlier days. I am sure many of you are familiar with Herbert Simon's seminal work on this, where...

In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else, a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes

Herbert Simon 1971

And that is attention.

Herbert Simon is operating in this kind of 1970s bureaucratic firm [scenario] - imagining people having to process information somewhat like computers, that if they have a lot of information to process, it is going to consume all their attention, and they will not have time to do other things. A simplistic, but very powerful framing that is still relevant. But we felt we were going up against the limits of this. Yes, attention can be scarce in certain settings, especially the settings that Herbert Simon is imagining. But it can also be abundant in many other ways. [Herbert's] attention economy metaphor does not always work...it obscures things as well as helps us explain things.

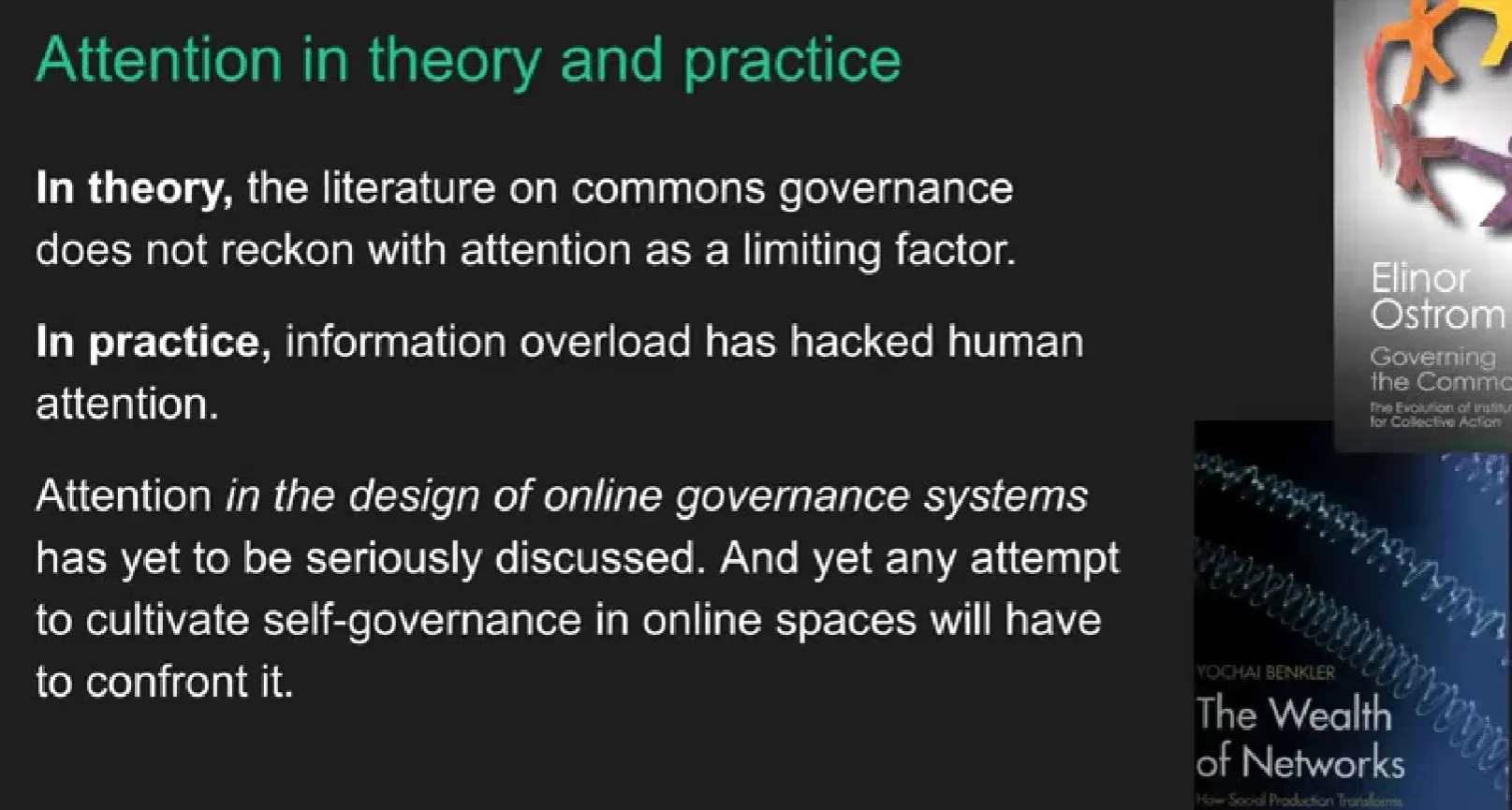

One place where we felt like we were moving beyond the traditional attention economy framing is when we started looking at the Commons literature. One of the prompts for me, for this paper, was reading a lot about Elinor Ostrom and Yochai Benkler, who were two central theorists of the Commons. And when you read their work, you can see that you have Herbert Simon telling us that attention is a resource, and it is; there are economies of attention. But on the other hand, we have these kinds of new ideas around how to govern new kinds of economies.

Elinor Ostrom has a lot of ideas about how Commons can be self-governing and how it is not all just a tragedy. And so she takes us away from some of the scarcity mindset, but at the same time, we were also seeing that they do not really reckon with attention as a limiting factor. So it is kind of trying to bring in some of the new economic thinking of the Commons, while also squaring it with attention.

Elinor Ostrom was mostly operating in pre-online community days. Yochai Benkler was quite sharp about seeing a lot of the things that came up with attention. He did talk about attention in his work, but neither of them looked at the idea of people participating in many spaces of governance, participating in many Commons at the same time, and having to manage that. Attention and governance are not something they focused on because it was not really a problem in the spaces they were thinking about.

So, in practice, we have this kind of information overload. In the context of governance, we started calling it governance overload, when you are participating in many spaces, and you do not really have time to get acquainted with all the proposals that are being submitted, all the context that you need to make effective decisions.

And what do we do about this?

This is the context for us coming into this work, where we are looking at these new online communities that are proliferating, and we really do not have the theories or practical design considerations to help us create self-governing online communities in ways that really respect and preserve human attention.

Mapping Information & Decision Flows

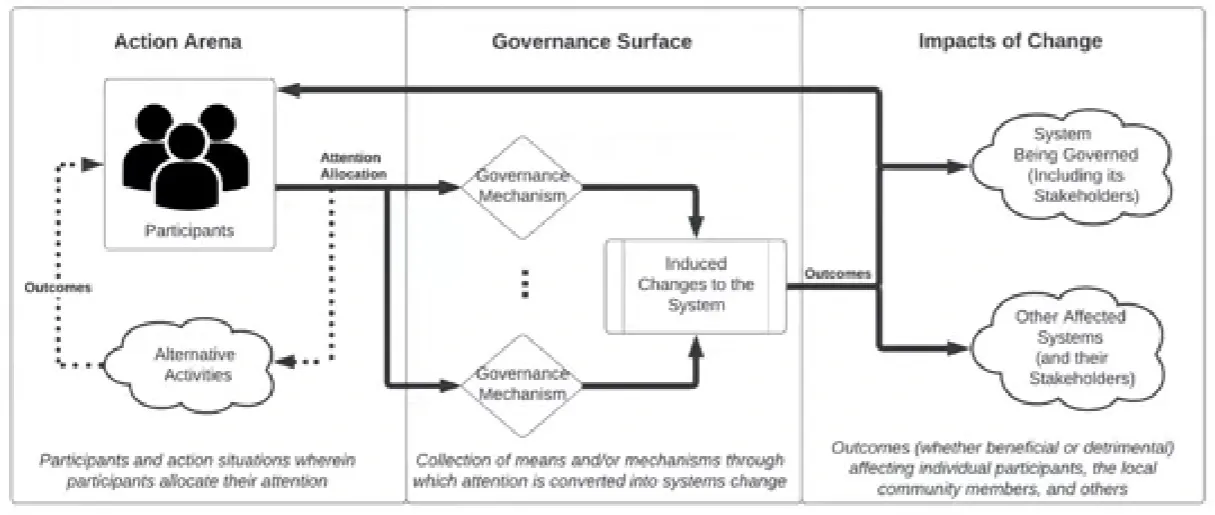

Governance surface: the means available for organizational adaptation and action. Attention economies: the analysis of human attention as a resource

[00:04:58] Zargham: One of the ways that we approach this methodologically, you could think of this as a mapping of information and decision flow. This diagram identifies the action arena, terminology taken from the Commons literature. This is the environment in which humans are making choices about what to spend their attention and effort on. They have to make a choice between, for example, participation in governance versus taking first-order activities within that organization, or participating in other environments. And given what Ronen and Nathan just laid out, we are observing that some of that choice is which governance environment to even participate in.

Then you have multiple mechanisms through which you might participate. That could be discussions on forums, that could be explicit voting mechanisms. It could be any number of activities that could be thought of as means of affecting the organization's trajectory of governing or steering it. And those activities are aggregated across multiple participants, often with different interests, preferences, and choices of modality. Changes within that system result in some kind of outcome. And it is worth noting that those outcomes are both on the system itself, so back around on those same people, it changes the structure, shape, or the lived experience in the action arena. There are also effects on other stakeholders.

Attention Scarcity & Abundance

So it is not only that we have many different landscapes in which to participate in governance in our modern, multi-landscape era that Nathan described at the beginning, they are coupled with each other, and we are making individual choices about which action arenas to participate in, how to participate in them, and ultimately those choices and activities feedback on those same action arenas. The idea is that these are not only closed loops, but they are plural in their sites.

Many individual participants are forced to choose between which landscapes and which modalities they participate in. This means that even though we have a generative, and again, this is the balance between these two theories, a generative hey, lots of people, lots of attention available, it is abundant, we can crowdsource this attention to create more than we would be able to without this diverse collection of participants.

Individuals are forced to choose how much time and effort to put into learning context, how deep to go into a particular governance modality, or even whether they want to participate in governance and to org level steering versus just participate or consume the thing that is being governed.

To Nathan's point earlier, that is the case in a lot of people's lives...I am happy to participate in governance of a few things, but most things that I have to trust that someone is doing that because I rely on their choices. I can only participate in governance for so many things. We can go to the next slide. This is probably Nathan's territory.

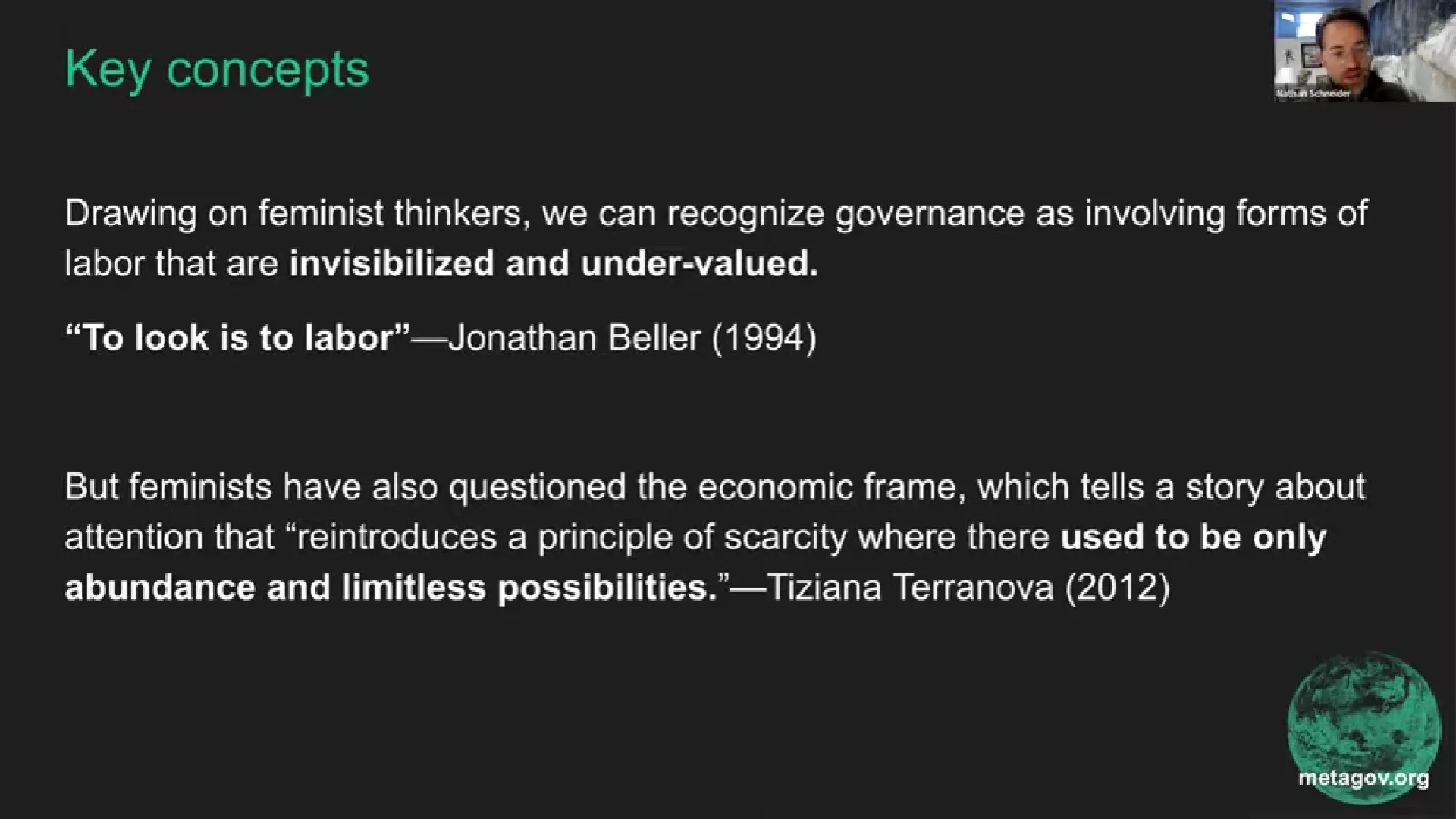

Risk Assessment: Attention as Labor

To look is to labor

Jonathon Beller 1994

While information was said to be a radically new type of commodity that challenged established economic models, attention seems to bring with it a recoding of the economy of new media along more orthodox lines, inasmuch as it reintroduces a principle of scarcity where there used to be only abundance and limitless possibilities. If information is bountiful, attention is scarce because it indicates the limits inherent to the neurophysiology of perception and the social limitations to time available for consumption.

Tiziana Terranova 2012

[00:07:49] Schneider: Yeah. This points to something Ronen spoke about earlier, which is the question about scarcity and abundance. One point that we turn to is the legacy of feminist economic thought around platforms. Recognizing that often there are forms of labor in platform economies and other economies that are invisibilized, and sometimes attention plays that role. So we need to be attentive to ways in which attention is being asked of people in ways that we are not recognizing and that we are not supporting. Recognizing that, for instance, attention can be a form of labor. That governance is a form of labor and that it not only needs to be noticed, but also provisioned for.

Part II: Case Studies in Web3 Governance

[00:08:29] Schneider: Okay, so the empirical heart of this project is a series of case studies in the context of Web 3.0, primarily because this is a space where attention and governance really first became a problem. Most online spaces do not offer a lot of opportunities for participants to do self-governance. I wrote a book about this. It is often not available in our online spaces, but in the context of blockchains and Web 3.0 projects, the idea that the participants would be co-owning their infrastructures raises this problem in a particularly acute way.

There are a lot of early projects and ongoing projects in this ecosystem that have been trying to contend with attention. We look at three different approaches, three different contexts where this has been happening. And these are things that we have mainly kind of participated in or experienced directly. So these are kind of, fairly informal but grounded case studies.

DAOstack & The Decentralized Governance Scalability Problem

[00:09:31] Tamari: Sure. So yeah, DAOstack was one of the case studies we looked at. I was a researcher for DAOstack for about a year in 2021. So I had firsthand experience with some of the events we were looking at, even though some of them also happened before my time there.

DAOstack was behind one of the first DAOs, the Genesis DAO. And they were building kind of the technical infrastructure, the stack, the tech stack for running DAOs. They identified the effective management of human attention as a key challenge to be addressed. And they called it the decentralized governance scalability problem. You can not scale up governance if you are not handling this idea of scale.

As more people join, there will be more proposals, and there needs to be some way to prioritize rank and filter those proposals. So they had an algorithm or a computational approach called holographic consensus. The idea was based on some form of mechanism design token staking. This was kind of the early Web 3.0 days. So there was a lot of techno optimism and thinking that with the right algorithm and the right smart contracts, we can solve all these, which are, in fact, very complex socio-technical problems.

But yeah, there is this idea of staking basically so that as proposals come in, people stake their reputation on whether they think the proposal will be passed or not. And then this leads to effective signaling of allocating attention to proposals that are more contentious or controversial. People can focus their attention on those proposals and ignore the ones that are simpler. So it is a great idea in theory, but in practice, what happened was that it did not really work the way they planned. First and foremost, just because the scale of the Genesis DAO was not big enough to warrant the heavy machinery of game theory. There were not many proposals being proposed, so they did not really need that.

What was missing were the social tools for deliberation and discussion, like forums, community building, and operations. There were some interviews, there is a great paper we referenced, a retrospective on DAOstack by Brekke et.al (2021l. They noted that there was a lack of an overarching mission with Genesis DAO. The whole point of that DAO was to use the tools that DAOstack was creating. They did not really have a purpose besides voting on proposals, and that hindered group cohesion.

It is a kind of early case and an example of how the over-financialization of attention in the governance of online communities can backfire. So it is like you are trying to solve it by adding more tokens and more layers of economics. And that is not necessarily going to play out the way you think, even though they probably have good ideas that we could be using around staking, reputation, and thinking about how to rank and sort proposals with computational mechanisms.

[00:12:18] Schneider: Do you want to go to the next one? I think it is interesting, for instance, I was at a DAO governance event recently where they were talking about prediction markets in very much the way that kind of mimicked what DAOstack was doing years ago, but now in a much larger DAO. So these ideas recur.

Gitcoin: Liquid Democracy & Stewards Council

A second case study is that of Gitcoin [a Web 3.0 and open source community grants platform], which, when it converted to a DAO, started out as a delegation system. So, building on this idea of liquid democracy, you delegate your stake to a smaller number of people who are going to direct more attention toward governance questions and vote on your behalf, and you could move that delegation whenever you wanted. But even that, they found it to be inadequate because people like me, who were brought in as stewards to whom people delegated votes, still did not have the context to really make decisions. The only vote I participated in was about pineapple pizza. Just because I did not feel like I ever had time to figure out what the heck these proposals were about and what was at stake.

They ended up creating some more social structures. They created a stewards council that would make sure that the top delegates had space and time to really understand the issues at play in the DAO. And so they ended up replicating patterns like a board to create dense interpersonal networks. They also create a reputation system where you could monitor your stewards through cards that would monitor their voting behavior. So they found that they had to develop more infrastructure to manage the attention economies than they initially anticipated.

Governatooorr: AI Voting Agents & Automated DAO voting

Finally, we look at automation. We looked at an early experiment in automated DAO voting, where you delegate your decision-making. Not to a person, but to an agent whom you have instructed ahead of time. The agent makes votes in the various DAOs based on inferences on the input you have given. It kind of moves the governance surface from actually making the votes directly to having to oversee this voting agent. It is unclear whether that ends up saving you time or resulting in decisions that you like.

But there is a lot of interesting work right now going on around agent-based democracy, both in context like DAOs as well as, for instance, in efforts around citizen assemblies and other kinds of more in-person governance where people are exploring how can we use AI techniques to streamline attention economies, like summarizing discussions so that if multiple simultaneous discussions are going on in an assembly, how can you synthesize those?

So this is very much, again, an active area of exploration, but we saw once again a case where the governance surface is being moved through automation.

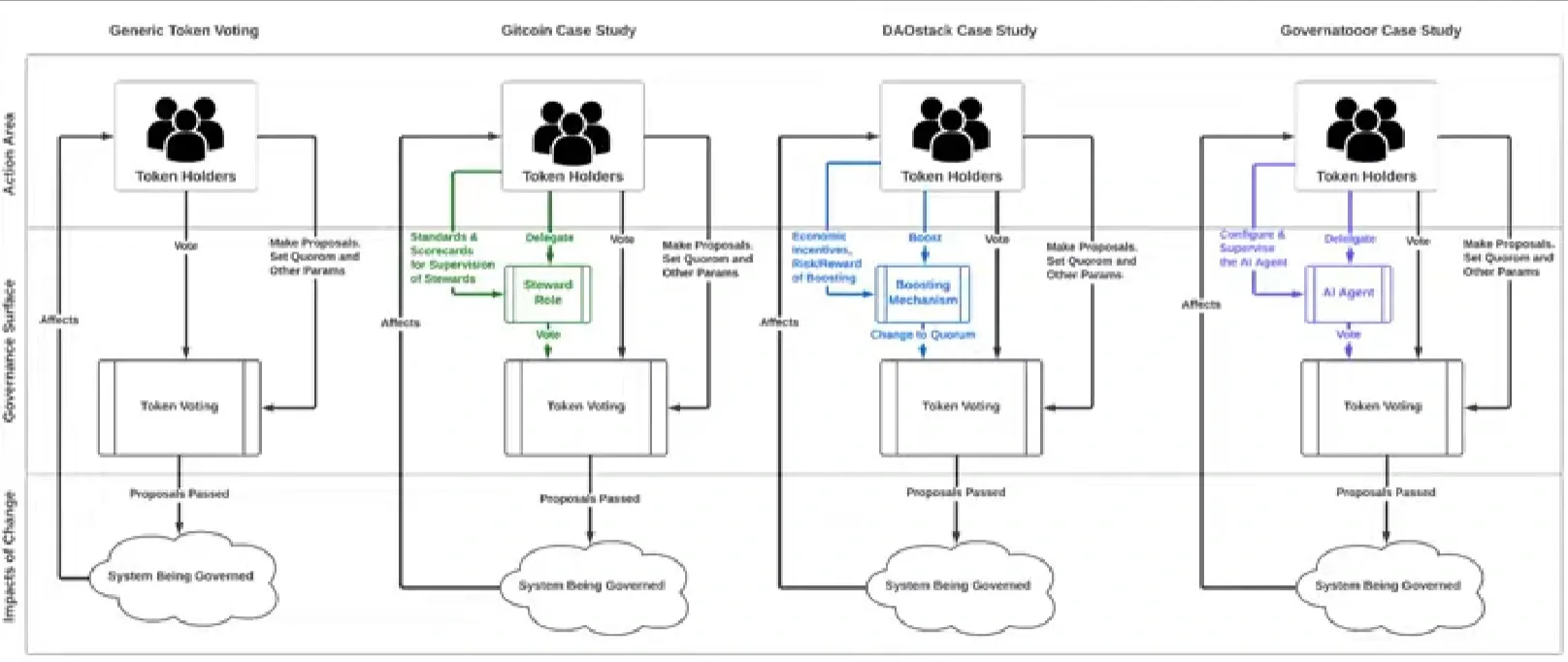

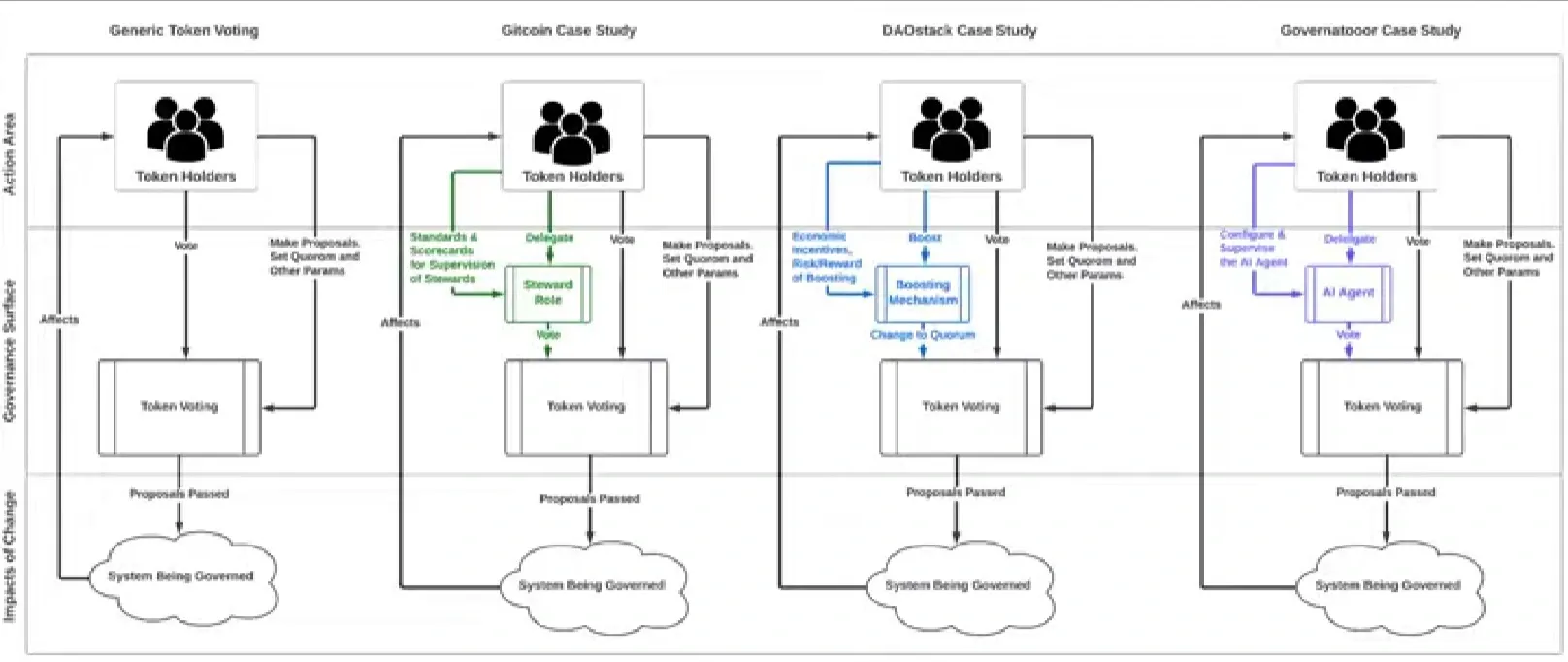

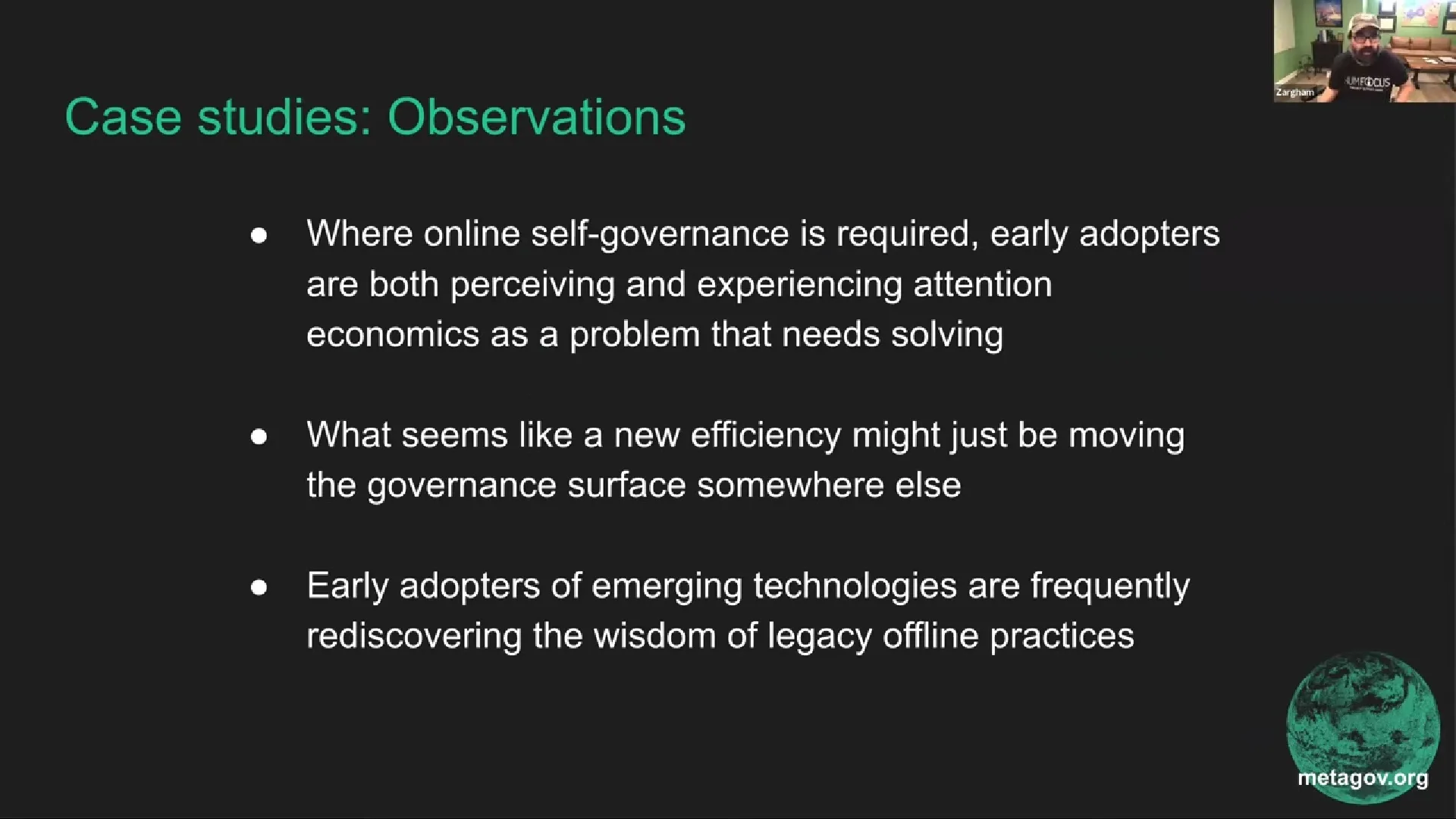

Case Study Observations

[00:15:05] Zargham: In the Web 3.0 use cases that we are exploring, there is a common base pattern where you have token holders, which are the parties with governance authority. The token is a representation of their right to participate in governance, regardless of whether that is financialized or non-transferable; you have a tokenized representation of governance, authority, and weight. But that still requires deliberative processes associated with agenda setting and figuring out what proposals are going to be on the docket, establishing various rules about what is required to pass a proposal, and then the need for individual actors to make sense of those proposals in context and to cast votes.

And what we have seen in this governance overload context is that it is a lot. And for reasons that people often participate in, many of them, especially in the Web 3.0 space, there was this governance overload and this constant need or desire or pain point to find a way to lighten that load. In each of these drawings, what is a mechanism by which that community attempted to change the shape of that governance surface to introduce an intervention, as it were?

In the Gitcoin case study, it was a steward role that was a kind of bottleneck in a more traditional human kind of score cards and a delegates way. In DAOstack, it was very algorithmic. A set of statistical protocols for determining the need for additional information. I think of that as an information-theoretic intervention.

And then you have a kind of modern AI sort of, "Hey, we have got these LLM agents, and if you load them up with enough context and give them enough instructions, they can make sense of all of that information for us." In my opinion, that has not been very effective for the reasons that Nathan alluded to, that people are not necessarily yet comfortable, qualified, or willing and able to expand the effort to then govern their agents.

But in all of these, and this is the common observation, the intervention did not actually eliminate the attention overload or eliminate a governance surface; it moved it.

We are seeing that the pain point has emerged in a common way. We are seeing that there is a desire or a need for maybe aggregate-level attention efficiency in the sense that, within a particular community, a certain amount of attention is available that has been volunteered, made available. And we need to find ways, at least in my opinion, to help communities and to empower communities, to help themselves recognize, to take stock of their attention, both in its abundance and in its constraints, and make things work locally. So if you go to the next slide.

Part III: Design Heuristics & Principles

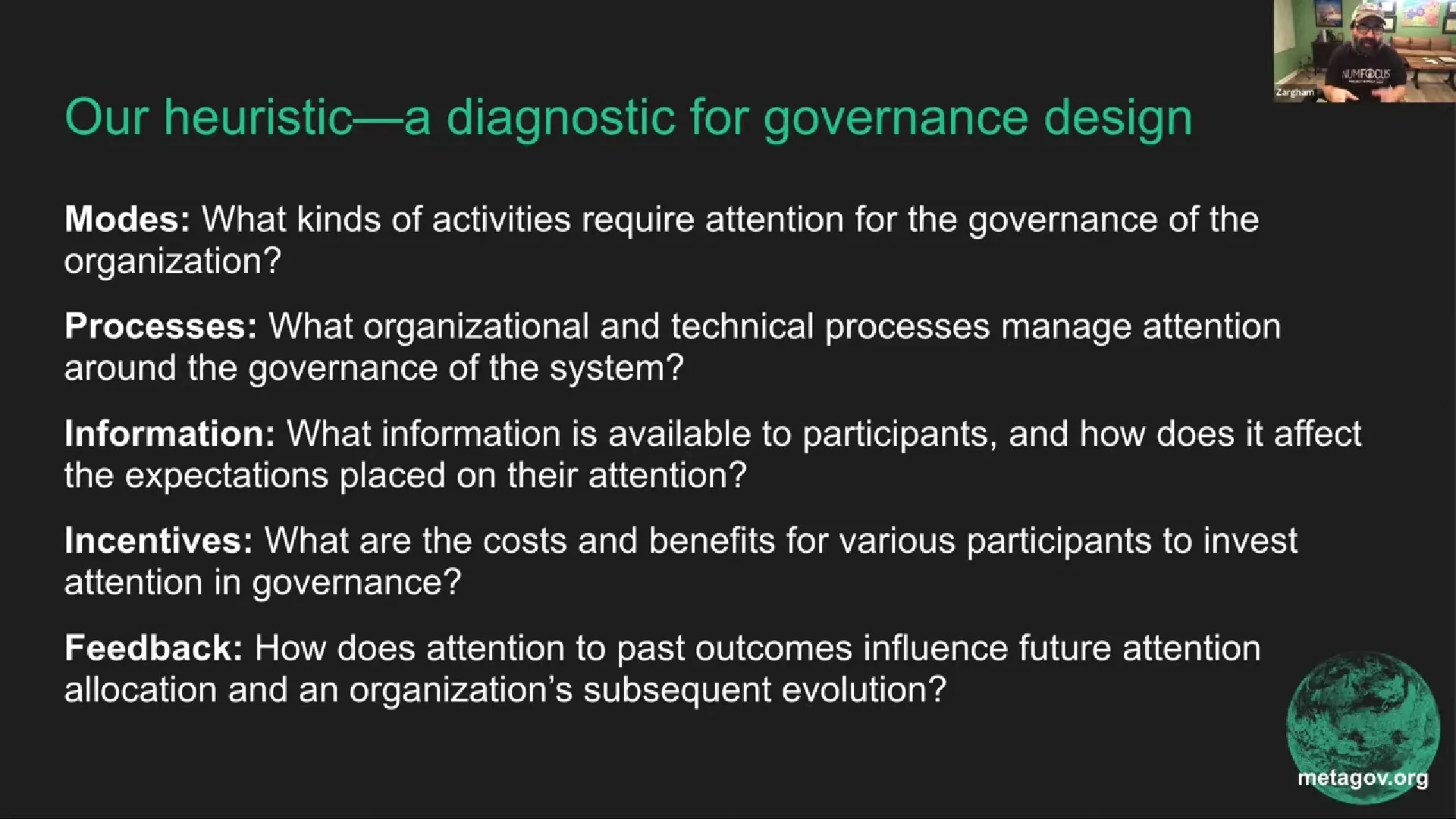

Five Heuristics for Governance Design

Modes: What kinds of activities require attention for the governance

of the organization? (Schneider et al., 2025)

[00:17:54] Zargham: The heuristics we have discussed are modes. This means being explicit about the modes through which governance is engaged with. And in some sense, this is making explicit the governance surface, the kinds of things that one can do that affect the steering of the organization, and our ability to be explicit about what they are, and our ability to give people guidance about how to participate in them.

Processes: What organizational and technical processes manage attention

around the governance of the system? (Schneider et al., 2025)

Processes relate to kind of both organizational and technical. You could think of this as the bureaucratic component in some sense. Rules, norms, and shared practices are implemented to turn attention into outcomes. In the Web 3.0 world, this is often very technical. But in a non Web 3.0 setting, we see a lot of this is just like a business process. It converts the effort that your communities and your stakeholders put into actual outcomes.

Information: What information is available to participants, and how does it affect the expectations placed on their attention? (Schneider et al., 2025)

Information is the information that we provide to people in order to become informed. The field of information design is itself kind of emerging. It was particularly present in the Gitcoin case study, where the development of these dashboards and scorecards, which provided information about the delegates, was an important feedback loop for selecting delegates. There is also information in terms of how we reflect an organization to its larger constituency, so people can decide when, where, and how to engage both as a participant and in governance.

Incentives: What are the costs and benefits for various participants

to invest attention in governance? (Schneider et al., 2025)

Incentives cover what we talked about as a kind of return on intention, like what kinds of costs and benefits...but also financial benefit perceptions that emerge within these contexts. I would separate this from processes in that processes are like strict rules in the sense of you follow the rules, whereas incentives are like, what? How you perceive the costs and benefits of what you put in and get out. From modes of participation.

Feedback: How does attention to past outcomes influence future attention

allocation and an organization’s subsequent evolution? (Schneider et al., 2025)

And I think possibly the most important is feedback. And it is really how this loops back around because these are not one-shot games. They are living systems made up of people, and tension is the lifeblood of those systems. And maybe that is me projecting my own pseudo-biological interpretation of organizations. But without a feedback process that gives rise to a continued injection of attention from the various stakeholders that make up a particular system, it becomes kind of a zombie.

And since we are talking about a Web 3.0 based empirical study, you can also look at other Web 3.0 based systems where eventually the attention bled out, and those are the zombie DAOs. I think we can move on from there. I want to make sure we get to discussions. Do you want to close this out, Nathan?

Attention: A Critical Element of Governance Design

[00:20:29] Schneider: Sure. The main idea here is that with these kinds of heuristics, we are trying to pose the question of how we think about attention in governance surfaces, and that we need to recognize attention as a critical aspect of design. If we are going to build more kinds of governance services in our online lives, we need to be compassionate about how we design around attention and be honest about what we expect. That we set expectations with our communities about what is appropriate, paying attention to what kinds of governance inputs they involve. And we found that often there are disconnects.

So how do we design around attention? We hope that these heuristics we have shared help people start to assess their own approaches to governance design, with an eye toward attention. To recognize that unexpected behavior, like a lack of participation, is a form of feedback about attention. We have often seen people blame their communities for what is actually a misdesigned detention economy.

And then finally, to make sure that we expect governance design around attention to evolve. Recognizing that attention economies change as the size and nature of an organization change.

I just love examples like this photo from one of the annual meetings that happen at the hundreds of rural electric cooperatives that function across the United States. People in communities co-own and cover their electrical grids. And at these meetings, I have been to them here in Colorado, they often have free food and games, and fun. These are ways of building the attention economy for this governance. Yes, they are going to vote on the board members at that meeting, but they are also enjoying a meal together. A free buffet in this case. To me, this is a small and simple example of how governance designs have been designed for attention all along.

If you go to the next slide, we just have a link to the paper. Thank you all so much for your attention. Looking forward to what kinds of issues you all want to bring up.

Part IV: Question & Answer Session

Shout Out! Digital Ethnographer Kelsie Nabben

[00:22:34] Michael Zargham: Quick shout-out for Kelsie! She did her dissertation work, wrapping it up around when we were writing this paper. She covered self-infrastructure and the topic of building and implementing these systems by and for our communities. I found her contributions around the ethnographic component of these feedback loops to the final point around lived experience, redesign, and recalibrating based on lived experience. That feedback loop heuristic is often implemented through human beings who are tracking, monitoring, writing, authoring, and sharing information to make organizations legible to themselves. And I think that is super important, and I wanted to give her an extra shout-out since we did not have her today.

Representative vs. Direct Democracy

[00:23:28] Jonathon: Did you look at questions about representative democracy as opposed to direct democracy? It is kind of my impression that what led to the invention of representative democracy was that things were too big and too complicated for all the citizens of Athens to get together and figure it out.

Schneider: I mean, the closest we come to it, looking at it in these Web 3.0 contexts, is through this delegation mechanism. And I think it is interesting that in some respects, Web 3.0 folks have been trying to get away from the representative logic. Seeing some of the ways in which representation can reproduce oligarchy. I think that is an aspiration in these kinds of communities.

Yet at the same time, in the Gitcoin case, the delegation mechanism ends up, in many ways, reproducing a representative function. And so I think it is an example of this kind of meme of the idea that Web 3.0 is speed running economic history? Recreating a lot of the institutions that they are trying to get away from and actually rediscovering the rationales for things like representation, as actually an attention economic design.

Simultaneous Temporal Modes

[00:24:45] Alex: I was curious about what efforts were made to look at things through a Daniel Kahneman system one and system two thinking. Knowing that your governance body can be split across different platforms.

Like in cryptocurrency, you have crypto Twitter, Discord, and Discourse, and they operate at different speeds. Especially looking at like your typical forum voting mechanisms and discourse, right? That is a little bit slower, a little bit more deliberative, and then the things that you see on like CT or Discord tend to be really high-paced. How much did you all look into that, and have you discovered any good mechanisms for bridging these two systems?

Zargham: I can jump in. I think that the Kahneman style, like the kind of individual psychological model of system one, system two, the kind of fast and reactive thinking, and the kind of slow, more deliberative thinking, has an interpretation at a kind of collective group level. But it is not a perfect match because, to your point, there is an even larger distribution of temporal modalities. You have very fast-paced stuff, but that does not actually directly result in enacting something, but it is still salient.

My intuition is that it would be prudent to do a temporal decomposition. I actually did some of that with work on Gitcoin many years ago, around fraud detection, where we did temporal decomposition of the modalities of work required for a community to do fraud detection.

For context, Kelsie and I were both involved in this before Gitcoin was a DAO. Shortly after it became a DAO, we were helping develop the sub-DAO responsible for fraud detection. There was a decomposition of that sub-DAO around the different modalities of work, ranging from near real-time application of the models to their maintenance, to the development and education of the community that maintained those models. And what you will see in any one of these settings is that there are like three, four, or five different temporal modes that need to be attended to simultaneously. And I would flag that under a category of work to be done along the vector that we have highlighted here to understand attention economies and governance across temporal skills.

Interoperable Systems & Attention

[00:26:54] Tamari:... there is something interesting here, which I wrote in the blog post that I linked in the chat. When you have interoperable systems, attention flows more naturally.

Social feedback would allow participants to see their contributions making a tangible difference, thus encouraging further sharing. Building this infrastructure according to FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles also means that, rather than be captured in platform siloes, attention data can easily flow across the ecosystem to inform other content recommendation and discovery services.

Oriel & Tamari (2025)

So, for example, you are talking about Discourse, Discord, all these social networks, right? LinkedIn. If these platforms are closed, it causes problematic dynamics with how attention flows because you have to look on LinkedIn to see what someone is saying. But in more interoperable worlds, for example, I am pretty active now in the Blue Sky App Pro community. And it is quite interesting to see how my activity in one app can actually be seen by other people in a different app. So you do not have this kind of fragmentation across apps, and that feels like a really important part of better information flows across apps.

Incentivizing Governance Participation

[00:27:37] Anon: Yeah. Thank you all so much. This was such fascinating work. I was so happy to see the potluck buffet slide at the end. I think that, like, really brings it back to the human side of the thing, not just like the technological solution. And mine is related, so I work in free software and work with a lot of free software communities. One problem we have is that people do not take the opportunity to participate. So I was wondering if you have any thoughts about building the attention economy muscles for communities, specifically in digital spaces, so that we are shaping that governable surface to the particular community.

[00:28:12] Schneider: I think I would just go back to recognizing that probably the answers are in our past, that it is kind of an old-fashioned thing. I think we imagine that with folk histories of things like Wikipedia and open source software, somebody just threw something on the internet and then everybody gathered and it magically happened, as opposed to people built organizations and seeded participation.

And that is why I think the spaces like Metagov, and for instance, Val was talking about play testing events earlier as something that we are actively organizing, and I think those matter, the kind of effort Val leads in building community in this space really matters. Because participation does not happen magically.

It has to be, to use a word from feminist economics - provisioned - you have to invest in creating spaces just like a corporation pays its board members, flies them out to fancy places, and feeds them fancy dinners. This is all part of investing in the practice of governance.

We need to dispense with the magical thinking that people are just going to show up and participate, and instead recognize, okay, what do we need to do in order to invite people to participate? What do we need to do to make sure that it is worth their while to participate? That they understand that there is a value in it for them, whether it is through community or financial remuneration, or something else. There are a lot of different ways to align to get those incentives right. It is a form of basic respect to recognize that people are not going to pitch into your thing just on their own. That one way or another, you are going to have to create something worthwhile for them.

Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation Trade-offs

[00:29:49] Michael Zargham: I want to riff on the comments in the chat regarding extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation. It is a well-known phenomenon in behavioral economics that extrinsic mechanisms like financial penalties and fees have a tendency to overwrite rather than be additive with more social and intrinsic motivation.

Abstract: The deterrence hypothesis predicts that the introduction of a penalty that leaves everything else unchanged will reduce the occurrence of the behavior subject to the fine. We present the result of a field study in a group of day‐care centers that contradicts this prediction. Parents used to arrive late to collect their children, forcing a teacher to stay after closing time. We introduced a monetary fine for late‐coming parents. As a result, the number of late‐coming parents increased significantly. After the fine was removed, no reduction occurred. We argue that penalties are usually introduced into an incomplete contract, social or private. They may change the information that agents have, and therefore, the effect on behavior may be opposite of that expected. If this is true, the deterrence hypothesis loses its predictive strength, since the clause “everything else is left unchanged” might be hard to satisfy.

Setting aside the Web 3.0 stuff for a moment, in my own experience, helping organize communities, again, food, parties, swag they play really important roles in the incentivization structure especially in places where from a business level, economic standpoint, it is actually impossible to make the dollars and cents that up that a lot of the normative and social value created in community and through governance enabling participatory governance is not something that you can make add up kind of hours based financial remuneration or assess on a basic capitalist economic return on investment model.

But it can still be a very real return on attention when you think about the other benefits. And that is, in my experience, created to make it concrete. I was the board president of a nonprofit where we had an annual meeting, we needed to get people to govern, and our annual meeting was coupled with our big summer barbecue party. That was how you created the incentive to participate in governance.

We would have a break to have the new people running for board or a general address, but it was a 45-minute carve out of what was otherwise five hours of hanging out in the city parks, grilling, and socializing. If that was a major budget line item for the organization, and that was not there because we wanted to have a party. I mean, we wanted to have a party; it was a necessary component of the incentives required to meet quorum for our governance to take place. Without that party, we would not meet a quorum.

Anon: You said that extrinsic motivations overwrite, and maybe you said that they are not additive. What did you mean when you said that they overwrite?

Zargham: Imagine you have a setting where the original, canonical reference was about people picking up their kids from daycare late. The social disincentive to pick up your kids late is very much present, but when they introduced a system of a financial fee, people perceived that as then having paid for the right to be late, and it actually increased rather than decreased the amount of lateness.

Mechanism design, like keeping track of who was late and broadcasting, amplified the normative incentive to not pick up your kids late rather than the financial fee, which gave people a sense that they had paid for the right to be late. And so that is a difference in mechanism design that completely flips the effect on the behavior.

Psychological Tactics

[00:32:44] Florian: Earlier, there was mention of liquid democracy. Whenever there is too little participation, we need to focus more on the attention economy. I was thinking it sounded like platforms like Temu, which work with the psychological traits and weaknesses of people... wouldn't that be an incentive for the people who organized this election to use all kinds of psychological tactics to make them participate?

Zargham: I think that in practice, governing organizations is really like muddling through. In my experience, for most people, governance is not something that they are really thinking about. It is a necessity. In the case of the example I gave about food and the party, part of that was just in the bylaws. We had quorum rules. We have to meet the quorum rules. We literally can not ratify a budget or elect new board members, like we can not do what we do, but people care about doing what we do, not governance as such.

There is a special character of a space like Metagov that is full of people who are really thinking hard about governance. But in the organizations I have been involved in, governance is not explicit. It is like it happens because it needs to happen, because there are bylaws and rules about how the organization is comported. But like, there is not necessarily a meta ongoing meta-analysis about the state of governance, if that makes sense.

Schneider: I think that is a really interesting case where that organization decided we are going to put in a poison pill force through this quorum. Force this participation and say this kind of participation matters. And I think what this paper asks is, where are you putting those designs in? Maybe the concern was, okay, the board is managing most governance, but we want to have at least one input a year where a large number of people step in. And I think that is a really important conscious decision.

And I think in any organization, we should ask, what are the things that are appropriate to do at a smaller scale with a smaller number of people with focused attention? And then what are the things where more dispersed attention is important? Is it too much to ask for that quorum, or is that a necessary kind of pain point to make sure that everybody in the organization feels that they are being called upon in some way?

And every organization has to ask that differently. I do not participate actively in the governance of my credit union. Most people do not. There are other communities where, like this social media cooperative I am part of, I do like to participate more actively because it is rewarding in those intrinsic ways. These are questions we should be asking ourselves intentionally, rather than what we hear: why are people not showing up? Why are people not voting in every single DAO decision that we have? Do you not care about our DAO? When the level of expectations compared to the voice that people really have is just out of alignment.

Zargham: And I invite everyone to pick two or three things in their life to really commit to being part of self-governance, but then let yourself off the hook for everything else. If everybody picks a few things and chooses to give attention to governance, it is very generative. Doing a good job is a lot of work.

Schneider: But it also requires aligning incentives to ensure that, you know, I did go to one of my credit union meetings, I have met with a board member, and I became satisfied through those interactions that this organization is set up to represent me, even though I am not actively involved. And that is something we also have to design for. I think incentive alignment is an important tool, not the only tool. Mission alignment is also really important, but we have to be willing to trust those institutional designs.

Zargham: The information design heuristic in our list is also potentially a key element of that. The incentives for you to feel confident that you are well represented and the lower cost of attention for you to come to that conclusion are part of designing the legibility, the information design part. I totally agree, and I think that is part of what the information heuristic represents in the paper.

Val @ Metagov: Malcolm asked Q: if we understand attention as both a response to Maslovian needs and a reaction to stress, then what ways could DAOs transform the attention economy, not just as a function of technology, but as a solution to the human needs themselves?

Zargham: That is a really big question to do in one minute.

Val @ Metagov: Yeah, I have a thought on it. My participation in DAOs, like at the peak of the DAO boom, was really entertaining because I was able to join a team where there was a task board, and I had an incentive to earn tokens by doing tasks on this board. And it was this distributed way of participating in governance, like bite-sized chunks of tasks that this organization made open, to a wide group of people.

I had never seen anything like that before. That DAO has since sunsetted. Like many, I think there was this overfinancialization problem at the core of it, but it was very transformational in my understanding of what is possible when it comes to organizing people, getting people to participate in things - whether it be big governance decisions or just retweet something - and earn a token. All organizations have things like that, ways of making participation more accessible, governance more accessible. It points to some potential avenues for growth even though that DAO has sunset.

Acknowledgments

This AI-aided post is based on the original ideas and content of research author(s) Nathan Schneider, Kelsie Nabben, Ronen Tamari, and Michael Zargham. And with their express permission, and support from the team at Metagov, this content is repurposed here with the assistance of AI video and audio editing tool Descript, LLMs - Claude, ChatGPT & Gemini - and humans in the loop for technical and editorial review, and publishing. Thank you to the presenters, Metagov participants, Jessica Zartler, and lee0007.