By Ellie Rennie

What makes an organisation distinct isn’t just its outputs; it’s the continual processes of ordering knowledge — what is flagged, what is forgotten, and what gets passed along (and to whom). Our ethnography tools aim to make those processes machine-readable, and provide groups with the ability to set boundaries that AI and other data products must operate within.

This article describes the evolution of the Telescope bot through the KOI protocol. Together, KOI and Telescope turn inputs from informal conversations within online community forums into organisational ordering and memory that can be continuously updated and used to implement procedures and boundaries for automated systems, including LLMs and agentic AI. Scroll to the end for a short demo.

What is KOI?

Knowledge Organisation Infrastructure (KOI) is an open architecture and protocol developed by BlockScience with input from Metagov. KOI enables groups to organise and share knowledge on their own terms, providing a common framework for diverse groups to indicate what they know and to voluntarily share information without forcing them into a single unified database, closed-source software, or sacrificing control over sensitive information [1].

At the heart of KOI are “reference identifiers” (or RIDs), a protocol also developed by BlockScience. RIDs are akin to library-style call numbers that provide a systematic way to point to something (known as a ‘knowledge object’, such as a chat message, a document, or a spreadsheet) without handing over the item itself. Anyone who has the label can locate and request the original knowledge object to discover what’s in it, yet the label alone never reveals the full content.

KOI nodes look after these labels. A node might collect new labels, update existing ones or remove them when the underlying material changes. When nodes exchange these three simple signals with other nodes — “new,” “update,” or “forget” (FUN) — they weave themselves into a KOI-net. In that network, every participant can refer to and discuss the same pieces of knowledge even if the files live on different servers, are offline/non-digital, or belong to different organisations, as long as they are using shared RID labels.

As such, KOI allows groups to share a common map of “what we know” without forcing anyone to surrender their data or conform to a unified or centralised system or ways of knowing. A KOI node within a KOI network can call data from another node (if permissions are in place to do so), process data into new knowledge objects, or act on other systems, such as outputting to a Slack channel. As BlockScience’s Michael Zargham describes it, KOI is like duct tape and WD-40 that can be used to connect the sites where information is stored and used so that the labels travel but the material stays where it is. It is this toolkit for “stitching together”, as opposed to raw data being hoovered up, that enables groups of people and software agents to coordinate, share knowledge sets, and add boundaries and context over how that occurs. Genuinely processing knowledge is key to understanding the significance of KOI. As David Sisson and Illan Ben-Meir from BlockScience have articulated, knowledge is achieved by continually organising and reorganising information, allowing us to link current actions with potential future outcomes.

As the KOI protocol’s job is to standardise how nodes talk to each other, not what each node does internally, groups remain free to encode their own rules and processes inside their KOI nodes. They can also set policies about what knowledge to share or not share externally by deciding which events to emit or which queries to answer. In the KOI-net beta demonstration, for example, five nodes (a coordinator, two sensors, two processors) self-assemble into a knowledge processing network, but this is just one configuration. Future KOI-nets could incorporate more complex arrangements, including community-defined rules at the node level or higher-level governance where multiple communities connect their KOI-nets with negotiated policies. The Telescope deployment is the first to venture into this territory.

Telescope: From bot to KOI-net

Telescope began as a simple qualitative data collection bot, designed to help overcome challenges that I and others in Metagov were facing in our research into onchain technologies and associated communities. Traditional ethnography involves a human researcher observing and taking notes, which doesn’t scale well to online communities where people can join and leave at any time, remain pseudonymous if they so choose, and where organisational knowledge is distributed across numerous platforms and places (e.g. Telegram, Slack, GitHub, blogs, voting platforms, the blockchain, and more). Lurking and logging conversations under these conditions can raise ethical issues, as participants may not be aware that research is taking place and could (in fact should) be suspicious of messages coming from unknown researchers. Telescope was first deployed as a Discord bot that could be invited into servers (i.e. Slack or Discord chat applications) to assist with data collection (first tested in this ethnography). It is now evolving into a contextual, rule-based knowledge collection infrastructure through the KOI-net protocol.

What sets Telescope apart from simple chat loggers is its consent mechanism and participative capabilities. Rather than vacuuming up all messages, Telescope relies on community members to explicitly flag which content is relevant to the research question. This is done via a 🔭 telescope emoji reaction. If someone in a participating Discord server considers a particular message to be important to the research, they can react to that message with the telescope emoji. The bot detects this and initiates a consent workflow: it will send a polite request via direct message to the author of the message, providing them with information about the project and asking for permission to include their content in the dataset. Only if the author gives consent will Telescope save that message to the research dataset and add it to a dedicated channel featuring approved collected posts where others can see the dataset evolve. Telescope can either be used by a researcher or by the organisation itself to crowdsource the curation of a qualitative dataset. In the latter, community/organisation members surface the insights they find noteworthy, a moderator approves the bot to make the request, and authors approve their inclusion. As we noted in this paper, Telescope can help communities preserve and gain a deeper understanding of their own history, as the collected discussions can later be analysed or reflected upon by the community itself, not just the researchers.

My early experiments with Telescope revealed its limitations, which we have begun addressing through KOI. Because a telescoped message can be misleading or lack meaning in isolation, it is the ethnographer’s job to situate the comment in its original context and connect it to broader themes and events. With the help of Matthew Green (Research Assistant at RMIT University), I began using Obsidian to import Telescope into Markdown files with specific fields to add contextual data (standardised using Obsidian’s template function) and links to other notes.

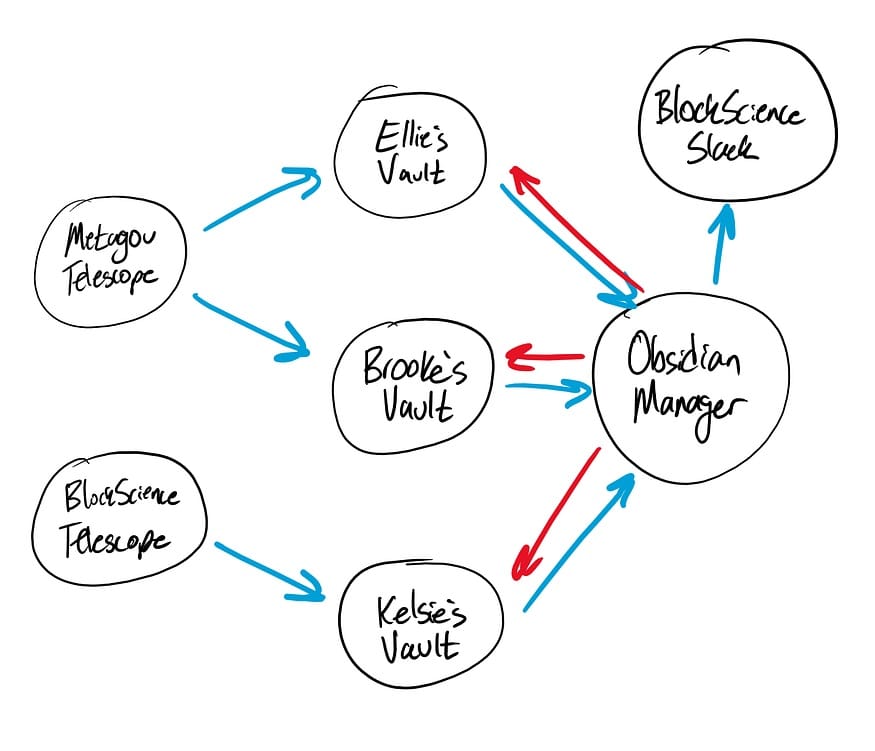

As we could not elegantly import Telescopes into Obsidian, we asked Metagov and BlockScience developer Luke Miller (who led the creation of Telescope and is now leading development of the KOI-net protocol) to build an Obsidian plugin. Luke suggested we first create a KOI node that receives Telescope data and sends only the approved messages to the researchers’ vaults, keeping any unapproved messages and data required for processing private. The resulting system enables the ethnographer to receive Telescopes into individual notes where they can easily add field observations, links and additional metadata. These Telescope notes can then be structured into maps of content along with other notes (including highlights and notes imported from reading software such as Zotero and Kindle, or content clipped from the web). The plugin syncs Telescope data and ensures that only those who have a key can access the data in the KOI node.

We have now further adapted the plugin so the ethnographer can send any kind of note (Telescope notes plus additional context, links, etc.) back to a KOI node and specify how it spreads through the network. For instance, a researcher using a KOI-augmented Obsidian vault can send notes that include the added ethnographic observations to other researchers on the team or to the community. How the community uses that data is then up to them. One possibility is that participants could query a collection of ethnographic observations using an LLM chatbot — essentially enabling community engagement with the research as it is happening. Alternatively, an LLM agent could subscribe to KOI events to receive live context as it is sent from the ethnographers, to help provide context for decision-making or feedback on a specific topic (see below).

Enacting Telescope

In summary, Telescope and KOI can help make organisational knowledge and its governance machine-readable so that it can be interacted with, including through AI. The trajectory of this capability as it progresses looks something like this:

- Telescope’s initial consent model is the first layer of governance in that no data enters the system without an individual’s permission.

- The community can specify policies for the Telescope sensor node. For instance, a DAO might collectively approve sharing a certain subset of Telescope-collected insights with another DAO alliance.

- Community members could join in analysis, developing an organisational reflective practice. Members might see patterns of their own activity (for example, “this week, discussions clustered around these themes”) derived from KOI-curated data. This could enhance self-awareness in organisations or communities and help them adapt governance in real-time. Because KOI can integrate with analytic tools and even AI, these insights could be generated automatically, but with clear provenance. Telescope and KOI can thus create real-time feedback loops between observation and action.

- Telescope could also be used as a form of contribution system by capturing contributions of knowledge through their reception. A contribution occurs not when the person adds the comment, but when someone else registers its importance by adding the telescope emoji or extending on the original post (like a citation). KOI’s RIDs make it easier to trace a piece of knowledge back to its origin and the chain of sorting and response (who collected it, who processed it). The community collectively filters and curates their knowledge, building a record of what is important (value creation) in the process.

- KOI’s ability to add context to a node provides a means to create checks-and-balances for autonomous agents and encoding context and procedures that the node is required to follow. This paves the way for AI integration that’s operating within community-set constraints.

Conclusion

In April, Benjamin Bratton, a Professor of Philosophy of Technology, posted OpenAI o3’s definition of “humans” to the social media platform X: “A self-modifying swarm of molecule-sized archivists that coax entropy into meaning by wrapping fleeting moments in elaborate chains of memory, prediction, and ritual”. If this is how an LLM views us, KOI-nets are an upgrade that makes a variety of such processes more machine-readable and controllable on the human side. o3’s definition captures how we humans create meaning through culture and then stabilise, scale, preserve or communicate it through organisations, systems and infrastructures. KOI-nets support this pattern-preserving impulse, making our group knowledge systems interoperable without compromising our control over our groupish human methods (rules, labels, organisations) for avoiding informational decay and entropy.

Demo

Credits

You can view the git repositories for KOI and for Telescope. Thanks to the following people for input into this post and for ongoing collaboration on the tools and concepts discussed.

ADM+S (RMIT node) researchers: Ellie Rennie, Matthew Green, Kelsie Nabben, Brooke Ann Coco. Jason Potts is leading the theory component of the project. BlockScience: Michael Zargham, Luke Miller, David Sisson Metagov: Elianna DeSota [1] For insight into why we use the term ‘knowledge’ rather than ‘data’, read Why is there Data? by BlockScience’s David Sisson and Ilan Ben-Meir.

Originally posted on Ellie's Medium account on September 11, 2025.